ナレンドラ ダモダルダス モディ नरेन्द्र दामोदरदास मोदी Narendra Damodardas Modi 1950 9 17生 18代インド首相 前グジャラート州首相

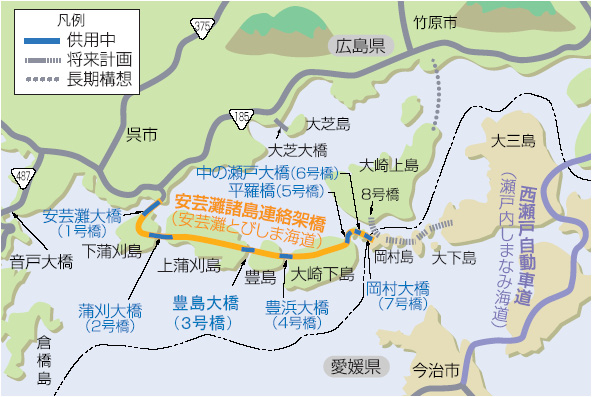

安芸灘諸島連絡架橋とは・・・

広島県呉市川尻町と、その南東に位置する安芸灘諸島を8つの橋梁で結ぶ計画です。

安芸灘諸島は、温暖で風光明媚な自然環境に恵まれており、柑橘類の生産や漁業が盛んに行われており、県民の浜など観光スポットも点在しています。

広島県では当地域の交通体系の整備を通じて、産業の振興、医療、教育及び文化などの生活環境の整備を進め、島しょ部住民の利便性の向上と定住基盤の整備を図るため、安芸灘諸島連絡架橋(1~8号橋)の建設を進めています。

また、当地域は、広島県の呉地方拠点都市地域・景観指定地域に指定されており、瀬戸内海特有の豊かな多島美を生かした観光開発の促進にも力を入れています。

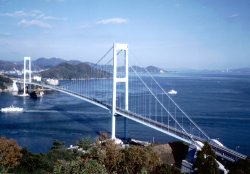

1号橋(安芸灘大橋)

1号橋(安芸灘大橋)

安芸灘諸島は、温暖で風光明媚な自然環境に恵まれており、柑橘類の生産や漁業が盛んに行われており、県民の浜など観光スポットも点在しています。

広島県では当地域の交通体系の整備を通じて、産業の振興、医療、教育及び文化などの生活環境の整備を進め、島しょ部住民の利便性の向上と定住基盤の整備を図るため、安芸灘諸島連絡架橋(1~8号橋)の建設を進めています。

また、当地域は、広島県の呉地方拠点都市地域・景観指定地域に指定されており、瀬戸内海特有の豊かな多島美を生かした観光開発の促進にも力を入れています。

1号橋(安芸灘大橋)

1号橋(安芸灘大橋)安芸灘諸島連絡架橋の事業概要

総延長:約5,300メートル(8橋)

区間:本土~下蒲刈島~上蒲刈島~豊島~大崎下島~岡村島~大崎上島

これまでの整備状況は・・・

これまでに、1号橋(安芸灘大橋)と3号橋(豊島大橋)が開通し、8つの橋梁のうち7つ(1~7号橋)が供用しています。

マザー・テレサ

カルカッタのテレサ | |

|---|---|

1995年6月にワシントンDCを訪問中のマザーテレサ | |

| 尼僧 | |

| 生まれ | AnjezëGonxheBojaxhiu 1910年8月26日Üsküp、Kosovo Vilayet、オスマン帝国(現在のスコピエ、北マケドニア) |

| 死亡しました | 1997年9月5日(87歳) カルカッタ、西ベンガル、インド (現在のコルカタ) |

| 崇拝 | ローマカトリック教会 |

| 列福 | 2003年10月19日、聖ペテロ広場、バチカン市国、教皇ヨハネパウロ2世 |

| 列聖 | 2016年9月4日、聖ペテロ広場、バチカン市国、教皇フランシスコ |

| 主要な神社 | 慈善宣教師の母の家、コルカタ、西ベンガル、インド |

| 饗宴 | 9月5日[1] |

| 属性 | |

| 後援 | |

| 題名 | 優れた将軍 |

| 個人的 | |

| 宗教 | カトリック |

| 国籍 | オスマン帝国の主題(1910–1912) セルビアの主題(1912–1915) ブルガリアの主題(1915–1918) ユーゴスラビアの主題(1918–1943) ユーゴスラビアの 主題(1943–1948)インドの主題(1948–1950) インドの市民[4](1950– 1997) アルバニア市民[5](1991–1997) 名誉アメリカ市民権(1996年受賞) |

| 宗派 | カトリック |

| サイン | |

| 研究所 | ロレット女子修道会 (1928–1948) 慈善宣教師 (1950–1997) |

| シニア投稿 | |

| 在職期間 | 1950〜 1997年 |

| 後継 | シニアニルマラ・ジョシー、MC |

マザー マリアテレサBojaxhiu [6] (生まれAnjezëGonxhe Bojaxhiu、アルバニア語: [aɲɛzəɡɔndʒɛbɔjadʒiu] ; 1910年8月26日- 1997年9月5日)、に光栄カトリック教会などカルカッタの聖テレサ、[7]だったアルバニア語-インド[ 4] ローマカトリックの 尼僧と宣教師。[8]彼女はスコピエ(現在は北マケドニアの首都)で生まれ、オスマン帝国のコソボヴィライェトの一部でした。。スコピエに18年間住んだ後、彼女はアイルランドに移り、次にインドに移り、そこで人生のほとんどを過ごしました。

1950年、テレサは、4,500を超える修道女を擁し、2012年に133か国で活動したローマカトリックの宗教会衆である「神の愛の宣教者」を設立しました。会衆は、HIV / AIDS、ハンセン病、結核で亡くなっている人々の家を管理しています。また、実行さ炊き出し、薬局、移動診療、子供や家族のカウンセリングプログラムだけでなく、孤児院や学校を。メンバーは、純潔、貧困、従順の誓いを立て、「貧しい人々の中で最も貧しい人々に心からの無料サービス」を提供するという4番目の誓いも公言します。[9]

テレサは、1962年のラモンマグサイサイ平和賞や1979年のノーベル平和賞など、数々の栄誉を受けました。彼女は2016年9月4日に列聖され、彼女の死の記念日(9月5日)は彼女のごちそうの日です。彼女の生涯と彼女の死後の物議を醸す人物、テレサは彼女の慈善活動のために多くの人から賞賛されました。彼女は、中絶や避妊に関する彼女の見解など、さまざまな点で賞賛され、批判されました。また、死にかけている彼女の家の状態が悪いことで批判されました。彼女の公認伝記はNavinChawlaによって書かれ、1992年に出版され、彼女は映画やその他の本の主題となっています。2017年9月6日、テレサと聖フランシスコザビエルは、カルカッタのローマカトリック大司教区の共同後援者に指名されました。

バイオグラフィー

若いころ

| 上のシリーズの一部 |

| インドのキリスト教 |

|---|

|

テレサはAnjezëGonxhe(またはGonxha)に生まれた[10] [必要なページ] Bojaxhiu(アルバニア語: [aɲɛzəɡɔndʒɛbɔjadʒiu] ; Anjezëがある同族の"アグネス"の; Gonxheは"バラのつぼみ"またはで"小さな花"を意味アルバニア語を)26に1910年8月、オスマン帝国(現在は北マケドニアの首都)のスコピエにあるコソバーアルバニアの家族[11] [12] [13]に。[14] [15]彼女は、生まれた翌日、スコピエでバプテスマを受けました。[10] [必要なページ]彼女は後に、バプテスマを受けた日である8月27日を「本当の誕生日」と見なしました。[14]

彼女はの末っ子だったNikollëとDranafile Bojaxhiu(Bernai)。[16]オスマン帝国のマケドニアでアルバニアのコミュニティ政治に関与していた彼女の父親は、1919年に8歳で亡くなりました。[14] [17]彼はプリズレン(現在はコソボ)で生まれましたが、彼の家族はミルディタ(現在のアルバニア)出身でした。[18] [19]彼女の母親はジャコーヴァ近くの村から来たのかもしれない。[20]

ジョアン・グラフ・クルーカスの伝記によると、テレサは幼い頃、宣教師の生活とベンガルでの奉仕の話に魅了されていました。12歳までに、彼女は自分が宗教生活に専念すべきであると確信していました。[21]彼女はの神社に祈ったとして彼女の決意は、1928年8月15日に強化黒い聖母のビティナ-Letnice彼女は、多くの場合に行ってきました、巡礼。[22]

テレサは、参加する18歳で1928年に家を出ロレートの姉妹でロレート修道院にラスファーナム宣教師になることを意図して英語を学ぶために、アイルランド。英語は、インドのロレット女子修道会の指導言語でした。[23]彼女は母親も妹も二度と見なかった。[24]彼女の家族は、1934年にティラナに引っ越すまでスコピエに住んでいた。[25]

彼女はに到着したインド1929年[26]と、彼女が始まった修練院でダージリン下で、ヒマラヤ、[27]彼女が学んだ場所ベンガル語を、彼女の修道院の近くに聖テレサの学校で教えていました。[28]テレサは1931年5月24日に最初の修道誓願を立てた。彼女は宣教師の守護聖人であるリジューのテレーズにちなんで名付けられることを選んだ。[29] [30]修道院の修道女はすでにその名前を選んでいたので、彼女はスペイン語の綴り(テレサ)を選びました。[31]

テレサは1937年5月14日、カルカッタ東部のエンタリーにあるロレート修道院学校の教師であったときに、厳粛な誓いを立てました。[14] [32] [33]彼女はそこで20年近く勤め、1944年に校長に任命された。[34]テレサは学校で教えることを楽しんだが、カルカッタで彼女を取り巻く貧困にますます不安を感じていた。[35] 1943年のベンガル飢饉は都市に悲惨と死をもたらし、1946年8月の直接行動の日はイスラム教徒とヒンズー教徒の暴力の期間を開始した。[36]

電車でダージリンを訪れている間、彼女は自分の内なる良心の呼びかけを聞いた。彼女は貧しい人々と一緒にいることによって貧しい人々に仕えるべきだと感じました。彼女は学校を辞めることを求め、許可を得た。1950年に彼女は「神の愛の宣教者」を設立しました。彼女は青い境界線のある2つのサリーで人類に奉仕するために出かけました。[37]

慈善の宣教師

1946年9月10日、テレサは、毎年恒例の撤退のためにカルカッタからダージリンのロレート修道院に電車で旅行したときに、後に「呼びかけの中の呼びかけ」と表現したことを経験しました。「私は修道院を出て、貧しい人々の間に住んでいる間、貧しい人々を助けることになっていました。それは命令でした。失敗することは信仰を破ることでした。」[38]ジョセフ・ラングフォードは後に、「当時は誰もそれを知らなかったが、シスター・テレサはマザー・テレサになったばかりだった」と書いた。[39]

彼女は1948年に貧しい人々との宣教活動を開始し[26]、彼女の伝統的なロレートの習慣を、青い縁取りのあるシンプルな白い綿のサリーに置き換えました。テレサはインドの市民権を採用し、パトナで数か月を過ごして聖家族病院で基本的な医療訓練を受け、スラム街に足を踏み入れました。[40] [41]彼女は貧しくて空腹の世話をする前に、コルカタのモティヒルに学校を設立した。[42] 1949年の初めに、テレサは若い女性のグループが彼女の努力に加わり、彼女は「貧しい人々の間で最も貧しい人々」を助ける新しい宗教的共同体の基礎を築いた。[43]

彼女の努力はすぐに首相を含むインド当局の注目を集めました。[44]テレサは彼女の日記に、彼女の最初の年は困難に満ちていたと書いた。収入がないので、彼女は食料と物資を懇願し、疑い、孤独、そしてこれらの初期の数ヶ月の間に修道院生活の快適さに戻りたいという誘惑を経験しました。

1950年10月7日、テレサは、慈善の宣教師となる教区会衆のバチカンの許可を受け取りました。[46]彼女の言葉では、「空腹、裸、ホームレス、不自由、盲人、ハンセン病、社会全体で望まれない、愛されていない、世話をされていない、すべての人々、重荷になっている人々を気遣うだろう」社会に、そして誰からも敬遠されている」。[47]

1952年、テレサはカルカッタ当局の助けを借りて最初のホスピスを開設しました。彼女は放棄されたヒンドゥー教の寺院を、貧しい人々のために無料で死を待つ人々の家に改宗させ、それを純粋な心の故郷であるカリガットと改名しました(NirmalHriday)。[48]家に連れてこられた人々は、彼らの信仰に従って、医療を受け、尊厳をもって死ぬ機会を得た。イスラム教徒はコーランを読み、ヒンズー教徒はガンジス川から水を受け取り、カトリック教徒は極度の機能を受け取った。[49]「美しい死」とテレサは、「動物のように生きた人々が天使のように死ぬことであり、愛され、欲しかった」と語った。[49]

彼女はハンセン病患者のためにホスピスを開き、シャンティナガル(平和の街)と呼んだ。[50]神の愛の宣教者たちは、カルカッタ全体にハンセン病アウトリーチクリニックを設立し、薬、包帯、食べ物を提供しました。[51]慈善宣教者は、ますます多くのホームレスの子供たちを受け入れた。1955年、テレサは孤児やホームレスの若者の避難所として、汚れなき御心の児童養護施設であるニルマラ・シシュ・バヴァンを開設しました。[52]

会衆は新兵と寄付を集め始め、1960年代までに、インド全土にホスピス、孤児院、ハンセン病療養所を開設しました。その後、テレサは会衆を海外に拡大し、1965年に5人の姉妹と共にベネズエラに家を開きました。[53]家屋は、1968年にイタリア(ローマ)、タンザニア、オーストリアで続き、1970年代に、会衆は、米国とアジア、アフリカ、ヨーロッパの数十か国に家屋と財団を開設しました。[54]

The Missionaries of Charity Brothers was founded in 1963, and a contemplative branch of the Sisters followed in 1976. Lay Catholics and non-Catholics were enrolled in the Co-Workers of Mother Teresa, the Sick and Suffering Co-Workers, and the Lay Missionaries of Charity. Responding to requests by many priests, in 1981 Mother Teresa founded the Corpus Christi Movement for Priests[55] and with Joseph Langford the Missionaries of Charity Fathers in 1984, to combine the vocational aims of the Missionaries of Charity with the resources of the priesthood.[56]

By 1997, the 13-member Calcutta congregation had grown to more than 4,000 sisters who managed orphanages, AIDS hospices and charity centers worldwide, caring for refugees, the blind, disabled, aged, alcoholics, the poor and homeless and victims of floods, epidemics and famine.[57] By 2007, the Missionaries of Charity numbered about 450 brothers and 5,000 sisters worldwide, operating 600 missions, schools and shelters in 120 countries.[58]

International charity

Teresa said, "By blood, I am Albanian. By citizenship, an Indian. By faith, I am a Catholic nun. As to my calling, I belong to the world. As to my heart, I belong entirely to the Heart of Jesus."[4] Fluent in five languages – Bengali,[59] Albanian, Serbian, English and Hindi – she made occasional trips outside India for humanitarian reasons.[60]

At the height of the Siege of Beirut in 1982, Teresa rescued 37 children trapped in a front-line hospital by brokering a temporary cease-fire between the Israeli army and Palestinian guerrillas.[61] Accompanied by Red Cross workers, she travelled through the war zone to the hospital to evacuate the young patients.[62]

1980年代後半に東ヨーロッパが開放性を高めたとき、テレサは慈善宣教者を拒否した共産主義国に彼女の努力を拡大しました。彼女は、中絶や離婚に反対する立場を批判することなく、何十ものプロジェクトを開始しました。「誰が何を言おうと、笑顔でそれを受け入れ、自分の仕事をするべきです」。彼女が訪れたアルメニアをした後、1988年の地震[63]とに会ったニコライ・ルイシコフ、会長の閣僚会議。[64]

テレサは、エチオピアの飢えた人々、チェルノブイリの放射線の犠牲者、アルメニアの地震の犠牲者を支援するために旅行しました。[65] [66] [67] 1991年に彼女は初めてアルバニアに戻り、ティラナにチャリティーブラザーズの宣教師の家を開いた。[68]

1996年までに、テレサは100か国以上で517のミッションを運営しました。[69]彼女の慈善宣教師は、12人から数千人に増え、世界中の450のセンターで「貧しい人々の最悪の人々」に奉仕しました。米国で最初のチャリティー宣教師の家がニューヨーク市のサウスブロンクス地域に設立され、1984年までに会衆は全国で19の施設を運営しました。[70]

健康と死の衰退

テレサは1983年にローマ教皇ヨハネパウロ2世を訪問中に心臓発作を起こしました。1989年の2回目の攻撃の後、彼女は人工ペースメーカーを受け取りました。1991年、メキシコでの肺炎の発作の後、彼女はさらに心臓の問題を抱えていました。テレサは慈善宣教者の長として辞任することを申し出ましたが、秘密投票で会衆の姉妹は彼女が留まることに投票し、彼女は続けることに同意しました。[71]

1996年4月、彼女は鎖骨を骨折して転倒し、4か月後にマラリアと心不全を発症しました。テレサは心臓手術を受けましたが、彼女の健康状態は明らかに低下していました。カルカッタヘンリーセバスチャンドゥーザの大司教によると、彼は彼女が悪魔に襲われているのではないかと思ったので、彼女が最初に心臓の問題で入院したときに(彼女の許可を得て)悪魔払いを行うように司祭に命じました。[72]

1997年3月13日、テレサは慈善宣教師の長を辞任し、9月5日に亡くなりました。[73]彼女の死の時点で、神の愛の宣教者には4,000人以上の姉妹がおり、123か国で610のミッションを運営している300人のメンバーの兄弟関係があった。[74]これらには、HIV / AIDS、ハンセン病および結核、炊き出し、子供および家族カウンセリングプログラム、孤児院および学校を持つ人々のためのホスピスおよび家が含まれていました。慈善の宣教師は、1990年代までに100万人を超える数の同僚によって支援されました。[75]

テレサは、葬式の前の1週間、カルカッタのセントトーマスにある開いた棺の中に横たわっていました。彼女は、インドのすべての宗教の貧しい人々への奉仕に感謝して、インド政府から国葬を受けました。[76] 5人の司祭の支援を受けて、教皇の代表であるアンジェロ・ソダノ国務長官が 最後の典礼を行った。[77]テレサの死は、世俗的で宗教的な共同体で悼まれた。パキスタンの首相ナワズシャリフ 彼女を「より高い目的のために長生きした珍しいユニークな個人。貧しい人々、病気の人々、そして不利な立場にある人々の世話に対する彼女の生涯にわたる献身は、私たちの人類への奉仕の最高の例の1つでした。」[78]元国連事務総長 ハビエル・ペレス・デ・クエラによれば、「彼女は国連である。彼女は世界の平和である」。[78]

認識と受信

インド

テレサは3世紀以上前にインド政府に最初に認められ、1962年にパドマシュリ勲章を、1969年にジャワハルラールネルー国際理解賞を受賞しました。[79]後に、バーラトラトナ(インドの1980年に最高の民間人賞)[80]テレサの公式伝記によって、ナヴィン・チャウラ、1992年に出版された[81]ではコルカタ、彼女はいくつかのことで神として崇拝されてヒンズー教徒。[82]

彼女の誕生100周年を記念して、インドの政府が特別に発行₹ 8月28日、2010年社長に5コイン(彼女はインドに到着したときにテレサが持っていたお金の量を)プラティバ・パティルは、Aと白いサリーをまとった」と言いました青い境界線、彼女と慈善の宣教師の姉妹は、多くの人々への希望の象徴になりました–高齢者、貧しい人々、失業者、病気の人々、末期の病気、そして彼らの家族によって捨てられた人々。」[83]

テレサに対するインドの見方は一様に好意的ではありません。カルカッタで生まれ育った医師で、英国に移住する前の1980年頃、市内のスラム街で活動家だったAroup Chatterjeeは、「これらのスラム街で修道女を見たことがない」と語った。[84]ボランティア、修道女、および慈善宣教者に精通している他の人々への100以上のインタビューを含む彼の研究は、テレサを批判する2003年の本に記載されていた。[84]チャタジーは、「苦しみのカルト」とカルカッタの歪んだネガティブなイメージを促進し、彼女の使命によって行われた仕事を誇張し、彼女の自由に使える資金と特権を悪用したことで彼女を批判した。[84] [85]彼によると、彼が批判した衛生上の問題のいくつか(例えば、針の再利用)は、1997年のテレサの死後に改善した。[84]

Bikash Ranjan Bhattacharya, mayor of Kolkata from 2005 to 2010, said that "she had no significant impact on the poor of this city", glorified illness instead of treating it and misrepresented the city: "No doubt there was poverty in Calcutta, but it was never a city of lepers and beggars, as Mother Teresa presented it."[86] On the Hindu right, the Bharatiya Janata Party clashed with Teresa over the Christian Dalits but praised her in death and sent a representative to her funeral.[87] Vishwa Hindu Parishad, however, opposed the government decision to grant her a state funeral. Secretary Giriraj Kishore said that "her first duty was to the Church and social service was incidental", accusing her of favoring Christians and conducting "secret baptisms" of the dying.[88][89] In a front-page tribute, the Indian fortnightly Frontline dismissed the charges as "patently false" and said that they had "made no impact on the public perception of her work, especially in Calcutta". Praising her "selfless caring", energy and bravery, the author of the tribute criticized Teresa's public campaign against abortion and her claim to be non-political.[90]

In February 2015 Mohan Bhagwat, leader of the Hindu right-wing organization Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, said that Teresa's objective was "to convert the person, who was being served, into a Christian".[91] Former RSS spokesperson M. G. Vaidhya supported Bhagwat's assessment, and the organization accused the media of "distorting facts about Bhagwat's remarks". Trinamool Congress MP Derek O'Brien, CPI leader Atul Anjan and Delhi chief minister Arvind Kejriwal protested Bhagwat's statement.[92]

Elsewhere

Teresa received the Ramon Magsaysay Award for Peace and International Understanding, given for work in South or East Asia, in 1962. According to its citation, "The Board of Trustees recognises her merciful cognisance of the abject poor of a foreign land, in whose service she has led a new congregation".[93] By the early 1970s, she was an international celebrity. Teresa's fame may be partially attributed to Malcolm Muggeridge's 1969 documentary, Something Beautiful for God, and his 1971 book of the same name. Muggeridge was undergoing a spiritual journey of his own at the time.[94] During filming, footage shot in poor lighting (particularly at the Home for the Dying) was thought unlikely to be usable by the crew. In England, the footage was found to be extremely well-lit and Muggeridge called it a miracle of "divine light" from Teresa.[95] Other crew members said that it was due to a new type of ultra-sensitive Kodak film.[96] Muggeridge later converted to Catholicism.[97]

Around this time, the Catholic world began to honour Teresa publicly. Pope Paul VI gave her the inaugural Pope John XXIII Peace Prize in 1971, commending her work with the poor, display of Christian charity and efforts for peace,[98] and she received the Pacem in Terris Award in 1976.[99] After her death, Teresa progressed rapidly on the road to sainthood.

She was honoured by governments and civilian organisations, and appointed an honorary Companion of the Order of Australia in 1982 "for service to the community of Australia and humanity at large".[100] The United Kingdom and the United States bestowed a number of awards, culminating in the Order of Merit in 1983 and honorary citizenship of the United States on 16 November 1996.[101] Teresa's Albanian homeland gave her the Golden Honour of the Nation in 1994,[90] but her acceptance of this and the Haitian Legion of Honour was controversial. Teresa was criticised for implicitly supporting the Duvaliers and corrupt businessmen such as Charles Keating and Robert Maxwell; she wrote to the judge of Keating's trial, requesting clemency.[90][102]

Universities in India and the West granted her honorary degrees.[90] Other civilian awards included the Balzan Prize for promoting humanity, peace and brotherhood among peoples (1978)[103] and the Albert Schweitzer International Prize (1975).[104] In April 1976 Teresa visited the University of Scranton in northeastern Pennsylvania, where she received the La Storta Medal for Human Service from university president William J. Byron.[105] She challenged an audience of 4,500 to "know poor people in your own home and local neighbourhood", feeding others or simply spreading joy and love,[106] and continued: "The poor will help us grow in sanctity, for they are Christ in the guise of distress".[105] In August 1987 Teresa received an honorary doctor of social science degree, in recognition of her service and her ministry to help the destitute and sick, from the university.[107] She spoke to over 4,000 students and members of the Diocese of Scranton[108] about her service to the "poorest of the poor", telling them to "do small things with great love".[109]

During her lifetime, Teresa was among the top 10 women in the annual Gallup's most admired man and woman poll 18 times, finishing first several times in the 1980s and 1990s.[110] In 1999 she headed Gallup's List of Most Widely Admired People of the 20th Century,[111] out-polling all other volunteered answers by a wide margin, and was first in all major demographic categories except the very young.[111][112]

Nobel Peace Prize

| External video | |

|---|---|

In 1979, Teresa received the Nobel Peace Prize "for work undertaken in the struggle to overcome poverty and distress, which also constitutes a threat to peace".[113] She refused the conventional ceremonial banquet for laureates, asking that its $192,000 cost be given to the poor in India[114] and saying that earthly rewards were important only if they helped her to help the world's needy. When Teresa received the prize she was asked, "What can we do to promote world peace?" She answered, "Go home and love your family." Building on this theme in her Nobel lecture, she said: "Around the world, not only in the poor countries, but I found the poverty of the West so much more difficult to remove. When I pick up a person from the street, hungry, I give him a plate of rice, a piece of bread, I have satisfied. I have removed that hunger. But a person that is shut out, that feels unwanted, unloved, terrified, the person that has been thrown out from society – that poverty is so hurtable [sic] and so much, and I find that very difficult."

Social and political views

Teresa singled out abortion as "the greatest destroyer of peace today. Because if a mother can kill her own child – what is left for me to kill you and you kill me – there is nothing between."[115]

Barbara Smoker of the secular humanist magazine The Freethinker criticised Teresa after the Peace Prize award, saying that her promotion of Catholic moral teachings on abortion and contraception diverted funds from effective methods to solve India's problems.[116] At the Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing, Teresa said: "Yet we can destroy this gift of motherhood, especially by the evil of abortion, but also by thinking that other things like jobs or positions are more important than loving."[117]

Criticism

According to a paper by Canadian academics Serge Larivée, Geneviève Chénard and Carole Sénéchal, Teresa's clinics received millions of dollars in donations but lacked medical care, systematic diagnosis, necessary nutrition and sufficient analgesics for those in pain;[118] in the opinion of the three academics, "Mother Teresa believed the sick must suffer like Christ on the cross".[119] It was said that the additional money might have transformed the health of the city's poor by creating advanced palliative care facilities.[120][121]

テレサの最も率直な批評家の1人は、英国のジャーナリスト、文学評論家、反神論者の クリストファーヒッチェンスであり、ドキュメンタリーHell's Angel(1994)のホストであり、2003年の記事に書いたエッセイThe Missionary Position:Mother Teresa in Theory and Practice(1995)の著者です。:「これは私たちを教会の中世の堕落に戻します。それは貧しい人々に地獄の火と禁欲を説きながら金持ちに耽溺を売りました。[マザーテレサ]は貧しい人々の友人ではありませんでした。彼女は貧困の友人でした。彼女は言った苦しみは神からの贈り物でした。彼女は、女性のエンパワーメントと強制的な複製の家畜版からの解放である、唯一知られている貧困の治療法に反対して人生を過ごしました。」[122]彼は、彼女の心臓病の高度な治療法を選択したことで偽善の罪で彼女を非難した。[123] [124]ヒッチェンズは、「彼女の意図は人々を助けることではなかった」と述べ、彼らの貢献がどのように使われたかについてドナーに嘘をついたと述べた。「私が発見したのは彼女と話をしたことであり、彼女は貧困を緩和するために働いていないことを私に保証した」と彼は言った。「彼女はカトリック教徒の数を増やすために働いていた。彼女は言った。ソーシャルワーカー。私はこのような理由のためにそれをしないでください。私はキリストのためにそれを行う。私は教会のためにそれを行う。 " " [125] Hitchensは、彼がによって呼び出されるだけの証人だと思ったが、バチカン、)テレサの列福と列聖に反対する証拠を提示するためにも呼ばれた。[126]バチカンは、同様の目的を果たした伝統的な「悪魔の代弁者」を廃止した。[126]

中絶権グループはまた、中絶と避妊に対するテレサの姿勢を批判しています。[127] [128] [129]

精神的な生活

教皇ヨハネパウロ2世は 、彼女の行いと業績を分析して、次のように述べています。彼の聖心。」[130]個人的に、テレサは彼女の人生の終わりまでほぼ50年続いた彼女の宗教的信念に疑いと闘争を経験しました。[131]テレサは、彼女の信仰の欠如に対する神の存在と苦痛について重大な疑いを表明した。

他の聖人(テレーズの同名のリジューのテレーズを含む、それを「無の夜」と呼んだ)は、同様の精神的な乾燥の経験をしました。[133]ジェームズ・ラングフォードによれば、これらの疑いは典型的なものであり、列聖の妨げにはならないだろう。[133]

10年間の疑念の後、テレサは短い期間の新たな信仰について述べました。1958年に教皇ピオ十二世が亡くなった後、彼女は「長い闇:その奇妙な苦しみ」から解放されたとき、レクイエムのミサで彼のために祈っていました。しかし、5週間後、彼女の精神的な乾燥は回復しました。[134]

テレサは、66年間にわたって、彼女の告白者や上司に多くの手紙を書きました。特に、カルカッタ大司教フェルディナンドペリエとイエズス会の司祭セレステファンエグゼム(慈善宣教者の設立以来の彼女の精神的顧問)に宛てました。[135]彼女は、「人々は私をもっと考え、イエスをもっと考えないだろう」と懸念して、手紙を破棄するよう要求した。[94] [136]

ただし、通信はマザーテレサ:来て私の光にまとめられています。[94] [137]テレサは、精神的な親友であるマイケル・ファン・デル・ピートに次のように書いています。聞いて聞いてはいけない–舌は[祈りの中で]動くが、話さない…私のために祈ってほしい–私が彼に[a]自由な手を持たせるように。」

でデウスカリタスEST(彼の最初の勅)、ベネディクト16世は、テレサを3回言及し、勅の主なポイントの一つを明確にするために彼女の人生を使用:「カルカッタの祝福テレサの例では、我々は時間が充てられているという事実を明確にイラストを持っています祈りの中で神に捧げることは、隣人への効果的で愛情深い奉仕を損なうだけでなく、実際、その奉仕の無尽蔵の源でもあります。」[138]彼女は、「私たちが祈りの賜物を育むことができるのは、精神的な祈りと精神的な読書によってのみです」と書いています。[139]

彼女の命令はフランシスコ会の命令とは関係がありませんでしたが、テレサはアッシジのフランシス[140]を賞賛し、フランシスコ会の精神性に影響を受けました。シスターズ・オブ・チャリティーは、コミュニオン後の感謝祭の間にミサで毎朝聖フランシスコの祈りを暗唱します、そして彼らのミニストリーへの強調と彼らの誓いの多くは似ています。[140]フランシスは、貧困、純潔、従順、そしてキリストへの服従を強調しました。彼は人生の多くを貧しい人々、特にハンセン病患者に奉仕することに捧げました。[141]

列聖

奇跡と列福

After Teresa's death in 1997, the Holy See began the process of beatification (the second of three steps towards canonisation) and Kolodiejchuk was appointed postulator by the Diocese of Calcutta. Although he said, "We didn't have to prove that she was perfect or never made a mistake ...", he had to prove that Teresa's virtue was heroic. Kolodiejchuk submitted 76 documents, totalling 35,000 pages, which were based on interviews with 113 witnesses who were asked to answer 263 questions.[142]

The process of canonisation requires the documentation of a miracle resulting from the intercession of the prospective saint.[143] In 2002 the Vatican recognised as a miracle the healing of a tumour in the abdomen of Monica Besra, an Indian woman, after the application of a locket containing Teresa's picture. According to Besra, a beam of light emanated from the picture and her cancerous tumour was cured; however, her husband and some of her medical staff said that conventional medical treatment eradicated the tumour.[144] Ranjan Mustafi, who told The New York Times he had treated Besra, said that the cyst was caused by tuberculosis: "It was not a miracle ... She took medicines for nine months to one year."[145] According to Besra's husband, "My wife was cured by the doctors and not by any miracle ... This miracle is a hoax."[146] Besra said that her medical records, including sonograms, prescriptions and physicians' notes, were confiscated by Sister Betta of the Missionaries of Charity. According to Time, calls to Sister Betta and the office of Sister Nirmala (Teresa's successor as head of the order) elicited no comment. Officials at Balurghat Hospital, where Besra sought medical treatment, said that they were pressured by the order to call her cure miraculous.[146] In February 2000, former West Bengal health minister Partho De ordered a review of Besra's medical records at the Department of Health in Kolkata. According to De, there was nothing unusual about her illness and cure based on her lengthy treatment. He said that he had refused to give the Vatican the name of a doctor who would certify that Monica Besra's healing was a miracle.[147]

During Teresa's beatification and canonisation, the Roman Curia (the Vatican) studied published and unpublished criticism of her life and work. Hitchens and Chatterjee (author of The Final Verdict, a book critical of Teresa) spoke to the tribunal; according to Vatican officials, the allegations raised were investigated by the Congregation for the Causes of Saints.[142] The group found no obstacle to Teresa's canonisation, and issued its nihil obstat on 21 April 1999.[148][149] Because of the attacks on her, some Catholic writers called her a sign of contradiction.[150]テレサは2003年10月19日に列福され、カトリック教徒には「祝福された」として知られていました。[151]

列聖

2015年12月17日、バチカン報道局は、教皇フランシスコがテレサに起因する2番目の奇跡を認識したことを確認しました。2008年に複数の脳腫瘍を患ったブラジル人男性の治癒です。[152]奇跡は最初に仮定の注目を集めました(当局者教皇がその7月にブラジルにいた2013年世界青年の日のイベント中に原因を管理する)。その後の調査は2015年6月19日から26日までブラジルで行われ、その後、列聖省に移管され、列聖省は調査の完了を認める法令を発行しました。[152]

フランシスは、2016年9月4日にバチカン市国のサンピエトロ広場で行われた式典で彼女を列聖しました。15人の政府代表団とイタリア全土からの1,500人のホームレスの人々を含む何万人もの人々が式典を目撃しました。[153] [154]それはバチカンチャンネルで生放送され、オンラインでストリーミングされた。テレサの故郷であるスコピエは、列聖の1週間にわたる祝賀会を発表しました。[153]インドでは、特別なミサがコルカタの慈善宣教師によって祝われた。[154]

カルカッタ大司教区の共同守護聖人

2017年9月4日、列聖の1周年を祝う祝賀会で、慈善宣教者のメアリー・プレマ・ピエリック姉妹は、テレサが大聖堂でのミサの間にカルカッタ大司教区の共同後援者になると発表しました。いとも聖なるロザリオの9月6日2017年の5.30 pmに[155] 2017年9月5日には、大司教トマスD'Souza氏の頭としての役割を果たす、カルカッタのローマカトリック大司教区は、テレサはの共同守護という名前になりますことを確認しましたカルカッタ大聖堂、フランシスザビエルと並んで。[156] [157] 2017年9月6日、ドミニク・ゴメスがいる大聖堂で約500人がミサに出席した。、地元の司教総代理[158]は、彼女を大司教区の2番目の守護聖人として制定した法令を読みました。[159] 式典はまた、ミサを率いて子供を乗せたマザーテレサ教会で銅像を発足させたD'Souzaとバチカンのインド大使であるGiambattistaDiquattroが主宰した。[159]

ローマカトリック教会は、1986年に聖フランシスコザビエルをカルカッタの最初の守護聖人と宣言しました。[159]

大衆文化における遺産と描写

記念

テレサは美術館によって記念され、多くの教会の愛国心と名付けられました。彼女は、アルバニアの国際空港を含む、彼女にちなんで名付けられた建物、道路、複合施設を持っています。10月19日のマザーテレサデー(DitaeNënëTerezës)は、アルバニアの祝日です。2009年、マケドニアの故郷スコピエにマザーテレサ記念館がオープンしました。ローマカトリック大聖堂でのプリシュティナ、コソボは、彼女の名誉で命名されました。[160]新築に道を譲るための歴史的な高校の建物の取り壊しは、当初、地元のコミュニティで論争を巻き起こしましたが、高校は後に新しい、より広々としたキャンパスに移転されました。2017年9月5日に奉献され、テレサに敬意を表して最初の大聖堂になり、コソボで2番目に現存する大聖堂になりました。[161]

マザー・テレサ女子大学、[162]でコダイカナルは、によって公立大学として1984年に設立されたタミル・ナードゥ州政府。マザーテレサ大学院健康科学研究所[163]は、ポンディシェリにあり、1999年にポンディシェリ政府によって設立されました。慈善団体Sevalayaは、マザーテレサガールズホームを運営しており、タミルナードゥ州のサービスの行き届いていないカスバ村の近くにいる貧しい孤児の少女たちに、無料の食料、衣類、避難所、教育を提供しています。[164]テレサの伝記作家、ナヴィン・チャウラによる多くの賛辞がインドの新聞や雑誌に掲載されています。[165] [166] [167] インド鉄道は、2010年8月26日に、マザーテレサの生誕100周年を記念して、マザーテレサにちなんで名付けられた新しい列車「マザーエクスプレス」を導入しました。[168]タミルナードゥ州政府はで2010年12月4日にテレサを称える周年のお祝いを整理チェンナイチーフ大臣が率いる、M M・カルナーニディ。[169] [170] 2013年9月5日から、彼女の死の記念日は国連総会によって国際チャリティーデーに指定されました。[171]

2012年、テレサはOutlookIndiaのGreatestIndianの投票で5位にランクされました。[172]

映画と文学

ドキュメンタリーと本

- テレサは、マルコム・マゲリッジによる1969年のドキュメンタリー映画と1972年の本「神にとって美しい何か」の主題です。[173]この映画は、マザーテレサに西洋の注目を集めたとされている。

- クリストファー・ヒッチェンズの1994年のドキュメンタリー、ヘルズ・エンジェルは、テレサが貧しい人々に彼らの運命を受け入れるように促したと主張している。金持ちは神に恵まれているように描かれています。[174] [175]それは、ヒッチェンズのエッセイ「宣教師の立場:理論と実践におけるマザーテレサ」の前身でした。

- Mother of The Century (2001) and Mother Teresa (2002) are short documentary films, about the life and work of Mother Teresa among the poor of India, directed by Amar Kumar Bhattacharya. They were produced by the Films Division of the Government of India.[176][177]

Dramatic films and television

- Mother Teresa appeared in Bible Ki Kahaniyan, an Indian Christian show based on the Bible which aired on DD National during the early 1990s. She introduced some of the episodes, laying down the importance of the Bible's message.[178]

- Geraldine Chaplin played Teresa in Mother Teresa: In the Name of God's Poor, which received a 1997 Art Film Festival award.[179]

- She was played by Olivia Hussey in a 2003 Italian television miniseries, Mother Teresa of Calcutta.[180] Re-released in 2007, it received a CAMIE award.[181]

- Teresa was played by Juliet Stevenson in the 2014 film The Letters, which was based on her letters to Vatican priest Celeste van Exem.[182]

- Mother Teresa, played by Cara Francis the FantasyGrandma, rap battled Sigmund Freud in Epic Rap Battles of History, a comedy rap YouTube series created by Nice Peter and Epic Lloyd. The Rap was released on YouTube 22 September 2019.[183]

- In the 2020 animated film Soul, Mother Teresa briefly appears as one of 22's past mentors.

See also

- Abdul Sattar Edhi

- Albanians

- List of Albanians

- List of female Nobel laureates

- The Greatest Indian

- Roman Catholicism in Albania

- Roman Catholicism in Kosovo

- Roman Catholicism in North Macedonia

References

- ^ "Canonisation of Mother Teresa – September 4th". Diocese of Killala. September 2016. Retrieved 4 September 2016.

- ^ Manik Banerjee (6 September 2017). "Vatican declares Mother Teresa a patron saint of Calcutta". Associated Press, ABC News.com. Archived from the original on 6 September 2017. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- ^ "Mother Teresa to be named co-patron of Calcutta Archdiocese on first canonization anniversary". First Post. 4 September 2017. Retrieved 5 September 2017.

- ^ a b c Cannon, Mae Elise (25 January 2013). Just Spirituality: How Faith Practices Fuel Social Action. InterVarsity Press. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-8308-3775-5. Retrieved 3 September 2016.

When asked about her personal history, Mother Teresa said: 'By blood, I am Albanian. By citizenship, an Indian. By faith, I am a Catholic nun. As to my calling, I belong to the world. As to my heart, I belong entirely to the Heart of Jesus.'

- ^ shqiptare, bota. "Kur Nënë Tereza vinte në Tiranë/2". Archived from the original on 18 September 2016. Retrieved 4 September 2016.

- ^ "Mother Teresa | Canonization, Awards, Facts, & Feast Day". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 18 May2017.

- ^ Poplin, Mary (28 February 2011). Finding Calcutta: What Mother Teresa Taught Me About Meaningful Work and Service. InterVarsity Press. p. 112. ISBN 9780830868483.

Remember, brother, I am a missionary and so are you.

- ^ Muggeridge (1971), chapter 3, "Mother Teresa Speaks", pp. 105, 113

- ^ a b Blessed Are You: Mother Teresa and the Beatitudes, ed. by Eileen Egan and Kathleen Egan, O.S.B., MJF Books: New York, 1992

- ^ Group, Salisbury (28 January 2011). The Salisbury Review, Volumes 19–20. InterVarsity Press. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-8308-3472-3.

Mother Teresa, Albanian by birth

- ^ "Mother Teresa". www.nytimes.com. Retrieved 18 May 2017.

- ^ Alpion, Gëzim (2006). Mother Teresa: Saint or Celebrity?. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 0-203-08751-8. Retrieved 15 November 2014.

the nun's mother was born in Prizren in Kosova, her family came originally from the Gjakova region, also in Kosova

- ^ a b c d (2002) "Mother Teresa of Calcutta (1910–1997)". Vatican News Service. Retrieved 30 May 2007.

- ^ "The Nobel Peace Prize 1979: Mother Teresa". www.nobelprize.org. Archived from the original on 11 October 2014. Retrieved 11 August 2012.

- ^ Lester, Meera (2004). Saints' Blessing. Fair Winds. p. 138. ISBN 1-59233-045-2. Retrieved 14 December 2008.

- ^ Although some sources state she was 10 when her father died, in an interview with her brother, the Vatican documents her age at the time as "about eight".

- ^ Lolja, Saimir (September 2007). "Nënë Tereza, katër vjet më pas". Jeta Katolike. Retrieved 25 May2020.

- ^ Mehmeti, Faton (1 September 2010). "Nënë Tereza dhe pretendimet sllave për origjinën e saj". Telegrafi. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- ^ "Moder Teresa" (in Danish). Retrieved 23 August 2010.

Hendes forældre var indvandret fra Shkodra i Albanien; muligvis stammede faderen fra Prizren, moderen fra en landsby i nærheden af Gjakova.

- ^ Clucas, Joan Graff. (1988). Mother Teresa. New York. Chelsea House Publications, p. 24. ISBN 1-55546-855-1.

- ^ Meg Greene, Mother Teresa: A Biography, Greenwood Press, 2004, p. 11.

- ^ Clucas, Joan Graff. (1988). Mother Teresa. New York. Chelsea House Publications, pp. 28–29. ISBN 1-55546-855-1.

- ^ Sharn, Lori (5 September 1997). "Mother Teresa dies at 87". USA Today. Retrieved 5 September 2016

- ^ Allegri, Renzo (11 September 2011). Conversations with Mother Teresa: A Personal Portrait of the Saint. ISBN 978-1-59325-415-5.

- ^ a b "From Sister to Mother to Saint: The journey of Mother Teresa". The New Indian Express. 31 August 2016. Retrieved 3 September 2016.

[Mother Teresa] came to India in 1929 ... she founded the Missionaries of Charity in 1948.

- ^ Clucas (1988), p. 31

- ^ Meg Greene, Mother Teresa: A Biography, Greenwood Press, 2004, page 17.

- ^ Sebba, Anne (1997).Mother Teresa: Beyond the Image. New York. Doubleday, p.35. ISBN 0-385-48952-8.

- ^ "Blessed Mother Teresa of Calcutta and St. Therese of Lisieux: Spiritual Sisters in the Night of Faith". Thereseoflisieux.org. 4 September 2007. Retrieved 24 August 2010.

- ^ Meg Greene, Mother Teresa: A Biography, Greenwood Press, 2004, page 18.

- ^ Spink, Kathryn (1997). Mother Teresa: A Complete Authorized Biography. New York. HarperCollins, p.16. ISBN 0-06-250825-3.

- ^ Clucas, Joan Graff. (1988). Mother Teresa. New York. Chelsea House Publications, p. 32. ISBN 1-55546-855-1.

- ^ Meg Greene, Mother Teresa: A Biography, Greenwood Press, 2004, page 25.

- ^ Spink, Kathryn (1997). Mother Teresa: A Complete Authorized Biography. New York. HarperCollins, pp.18–21. ISBN 0-06-250825-3.

- ^ Spink, Kathryn (1997). Mother Teresa: A Complete Authorized Biography. New York. HarperCollins, pp.18, 21–22. ISBN 0-06-250825-3.

- ^ tejash(2020年6月16日)。「マザーテレサに関するパラグラフ3マザーテレサに関するベストエッセイ-SarkariNaukri」。2021年2月8日取得。

- ^ クルーカス、ジョアングラフ。(1988)。マザーテレサ。ニューヨーク。チェルシーハウス出版物、p。35. ISBN 1-55546-855-1。

- ^ ラングフォード、ジョセフ(2008年10月)。マザーテレサの秘密の火:彼女の人生を変えた出会い、そしてそれがあなた自身をどのように変えることができるか。私たちの日曜日のビジター出版。NS。 44。ISBN 978-1-59276-309-2。2011年9月9日取得。

- ^ クルーカス、ジョアングラフ。(1988)。マザーテレサ。ニューヨーク。チェルシーハウス出版物、p。39. ISBN 1-55546-855-1。

- ^ 「祝福されたマザーテレサ」。ブリタニカ百科事典オンライン。ブリタニカ百科事典。2006年1月28日にオリジナルからアーカイブされました。2007年12月20日取得。

- ^ クルーカス、ジョアングラフ。(1988)。マザーテレサ。ニューヨーク。チェルシーハウス出版物、48〜49ページ。ISBN 1-55546-855-1。

- ^ 「マザーテレサ–ReligionFacts」。www.religionfacts.com 。取得した20年12月2016。

- ^ ウィリアムズ、ポール(2002)。マザーテレサ。インディアナポリス。アルファブック、p。57. ISBN 0-02-864278-3。

- ^ Spink、Kathryn(1997)。マザーテレサ:完全な公認伝記。ニューヨーク。ハーパーコリンズ、p.37。ISBN 0-06-250825-3。

- ^ ウィリアムズ、ポール(2002)。マザーテレサ。インディアナポリス。アルファブック、p。62 ISBN 0-02-864278-3。

- ^ 「washingtonpost.com:マザーテレサの人生のハイライト」。www.washingtonpost.com 。取得した20年12月2016。

- ^ セバ、アン(1997)。マザーテレサ:イメージを超えて。ニューヨーク。ダブルデイ、58〜60ページ。ISBN 0-385-48952-8。

- ^ a b Spink、Kathryn(1997)。マザーテレサ:完全な公認伝記。ニューヨーク。ハーパーコリンズ、p.55。ISBN0-06-250825-3。

- ^ セバ、アン(1997)。マザーテレサ:イメージを超えて。ニューヨーク。ダブルデイ、62〜63ページ。ISBN 0-385-48952-8。

- ^ 「マザーテレサ」。www.indianideology.com。2013年11月9日にオリジナルからアーカイブされました。取得した11年8月2012。

- ^ クルーカス、ジョアングラフ。(1988)。マザーテレサ。ニューヨーク。チェルシーハウス出版物、58〜59ページ。ISBN 1-55546-855-1。

- ^ Spink、Kathryn(1997)。マザーテレサ:完全な公認伝記。ニューヨーク。ハーパーコリンズ、p.82。ISBN 0-06-250825-3。

- ^ Spink、Kathryn(1997)。マザーテレサ:完全な公認伝記。ニューヨーク。ハーパーコリンズ、pp.286–287。ISBN 0-06-250825-3。

- ^ 「カルカッタの祝福されたマザーテレサによって設立された聖職者を切望する神の民。司祭のためのコーパスクリスティ運動」。Corpuschristimovement.com 。取得した3月14日に2013。

- ^ 「マザーテレサによって設立された司祭の宗教的共同体。慈善の父の宣教師」。2016年2月11日にオリジナルからアーカイブされました。2007年3月6日取得。

- ^ Spink、Kathryn(1997)。マザーテレサ:完全な公認伝記。ニューヨーク。ハーパーコリンズ、p.284。ISBN 0-06-250825-3。

- ^ Slavicek、ルイーズ(2007)。マザーテレサ。ニューヨーク; インフォベース出版、90〜91ページ。ISBN 0-7910-9433-2。

- ^ 「マザーテレサ」。bangalinet.com 。取得した3年9月2012。

- ^ 「マザーテレサについて知っておくべきトップ10の事柄」。biographycentral.net。2011年8月24日にオリジナルからアーカイブされました。取得した3年9月2012。

- ^ CNNスタッフ、「マザーテレサ:プロフィール」、2007年5月30日にCNNオンライン[リンク切れ]から取得

- ^ クルーカス、ジョアングラフ。(1988)。マザーテレサ。ニューヨーク。チェルシーハウス出版物、p。17. ISBN 1-55546-855-1。

- ^ ミレーナ、ファウストヴァ(2010年8月26日)。「マザーテレサのロシアの記念碑」。2013年2月18日にオリジナルからアーカイブされました。取得した13年9月2012。

- ^ 「マザーテレサとニコライルイシコフ」。1988年12月20日。2013年8月11日のオリジナルからアーカイブ。取得した13年9月2012。

- ^ クーパー、ケネスJ.(1997年9月14日)。「マザーテレサは、マルチフェイストリビュートの後に休息しました」。ワシントンポスト。2007年5月30日取得

- ^ 「奉仕の召命」。永遠のWordのテレビネットワーク アーカイブで2016年1月24日ウェイバックマシン

- ^ アルメニアのインド大使館公式ウェブサイト。大地震の後、1988年12月にマザーテレサがアルメニアにどのように旅したかを説明します。彼女と彼女の会衆はそこに孤児院を設立しました。2007年5月30日取得。 2007年3月20日ウェイバックマシンでアーカイブ

- ^ 「アルバニアの歴史:MCの熟考」。www.mc-contemplative.org 。取得した16年12月2016。

- ^ ウィリアムズ、ポール(2002)。マザーテレサ。インディアナポリス。Alpha Books、pp。199–204。ISBN 0-02-864278-3。

- ^ クルーカス、ジョアングラフ。(1988)。マザーテレサ。ニューヨーク。チェルシーハウス出版、頁104 ISBN 1-55546-855-1。

- ^ 「祝福されたマザーテレサ」。ブリタニカ百科事典。取得した13年9月2012。

- ^ Bindra、Satinder(2001年9月7日)。「大司教:マザーテレサは悪魔払いを受けました」。CNNは2007年5月30日に取得されました。

- ^ 「マザーテレサの後継者となるインド生まれの尼僧」。cnn。1997年3月13日。取得した13年9月2012。

- ^ 「マザーテレサのために消灯」。Bernardgoldberg.com。2010年8月23日。取得した3月25日に2012。

- ^ 「1979年ノーベル平和賞」。

- ^ AP通信(1997年9月14日)。「「インドは国葬で修道女を称える」。2005年3月6日にオリジナルからアーカイブされました。"。ヒューストンクロニクル。2007年5月30日取得。

- ^ 「バチカンの国務長官はマザーテレサの葬式で敬意を表する」。Rediff.com。1997年9月14日。2018年10月29日取得。

- ^ a b 記念碑、クリスチャン。「カルカッタ追悼サイトのマザーテレサ」。www.christianmemorials.com。2017年5月18日取得。

- ^ "Nehru Award Recipients | Indian Council for Cultural Relations | Government of India". www.iccr.gov.in. Archived from the original on 6 April 2018. Retrieved 18 May 2017.

- ^ "List of Recipients of Bharat Ratna" (PDF). Ministry of Home Affairs. 14 May 2015.

- ^ Chawla, Navin (1 March 1992). Mother Teresa: The Authorized Biography. Diane Publishing Company. ISBN 9780756755485.

- ^ Stacey, Daniel (3 September 2016). "In India, Teresa Draws Devotees of All Faiths". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved 18 May 2017.

- ^ "Commemorative coin on Mother Teresa released – Times of India". The Times of India. Retrieved 18 May 2017.

- ^ a b c d Schultz, Kai (26 August 2016). "A Critic's Lonely Quest: Revealing the Whole Truth About Mother Teresa". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 18 May 2017.

- ^ Chatterjee, Aroup, Introduction to The Final Verdict

- ^ "Was Mother Teresa a saint? In city she made synonymous with suffering, a renewed debate over her legacy". Los Angeles Times. 2 September 2016. ISSN 0458-3035. Retrieved 18 May 2017.

- ^ ディッカー、クリス。マザーテレサの伝記:世界を変えた献身的な魂の光。クリスディッカー。

- ^ 無私の思いやりの生活–最前線(雑誌)の記事。

- ^ 「秘密の洗礼」。Usislam.org 。取得した28年8月2011。

- ^ a b c d パールヴァティー・メノンカバーストーリー:無私の思いやりのある生活、最前線、Vol.14 :: No. 19 :: 1997年9月20日〜10月3日

- ^ ダール、アーティ。「マザーテレサの目的は回心でした」とBhagwatは言います。ヒンドゥー。2017年5月18日取得。

- ^ 「RSSはマザーテレサに関するモハンバグワットの首長の発言を支持し、反対派は彼を激しく非難します-Timesofap.com」。tsjzcra.timesofap.com。2018年4月9日にオリジナルからアーカイブされました。2017年5月18日取得。

- ^ Ramon Magsaysay Award Foundation(1962)マザーテレサの引用。

- ^ a b c Van Biema、David(2007年8月23日)。「マザーテレサの信仰の危機」。時間。2007年8月25日にオリジナルからアーカイブされました。2007年8月24日取得。

- ^ セバ、アン(1997)。マザーテレサ:イメージを超えて。ニューヨーク。ダブルデイ、80〜84ページ。ISBN 0-385-48952-8。

- ^ アルピオン、ゲズミン(2007)。マザーテレサ:聖人または有名人?。ラウトレッジ押し、頁9. ISBN 0-415-39246-2。

- ^ 「マルコムマゲリッジの霊的進化」。www.thewords.com 。取得した20年12月2016。

- ^ クルーカス、ジョアングラフ。(1988)。マザーテレサ。ニューヨーク。チェルシーハウス出版物、81-82ページ。ISBN 1-55546-855-1。

- ^ Quad City Timesのスタッフ(2005年10月17日)。「テリスの名誉でPacemを受け取る生息地の役人」。平和部隊。2007年5月26日取得。

- ^ 「それは名誉です:AC」。Itsanhonour.gov.au。1982年1月26日。2011年5月26日のオリジナルからアーカイブ。取得した24年8月2010年。

- ^ 「マザーテレサとしても知られるAgnesGonxhaBojaxhiuに米国の名誉市民権を授与する共同決議」。

- ^ ラウドン、メアリー(1996年1月6日)。「宣教師の立場:理論と実践におけるマザーテレサ、書評」。BMJ。312(7022):64–5。土井:10.1136 /bmj.312.7022.64a。S2CID 58762491。

- ^ カルカッタのマザー・テレサ、Fondazione Internazionale Balzan、1978年バルザン賞の人類、平和、そして人々の兄弟愛。5月26日2007年取り出さアーカイブで2006年5月14ウェイバックマシン

- ^ ジョーンズ、アリス&ブラウン、ジョナサン(2007年3月7日)。「反対派は引き付ける?ロバート・マクスウェルがマザー・テレサに会ったとき」。インデペンデント。2012年3月25日取得。

- ^ B 「ロングセンターでマザー・テレサアドレス4500」。カトリックライト。スクラントン大学デジタルコレクション。スクラントン大学。1976年5月1日。取得した28年4月2015。

- ^ カネラ、トニー(1976年4月28日)。「マザーテレサは地元の市民に愛を広め、心の貧しい人々を助けるように頼みます」。スクラントンタイムズ。スクラントン大学デジタルコレクション。スクラントン大学。取得した28年4月2015。

- ^ コナーズ、テリー(1987年10月)。「マザーテレサ社会名誉学位」。ノースイーストマガジン。スクラントン大学デジタルコレクション。スクラントン大学。取得した28年4月2015。

- ^ ピファー、ジェリー(1987年9月6日)。「スクラントンのマザーテレサ」。スクラントニアン。スクラントン大学デジタルコレクション。スクラントン大学。取得した28年4月2015。

- ^ 「大きな愛をもって小さなことをする:マザーテレサグレイセス教区」。カトリックライト。スクラントン大学デジタルコレクション。スクラントン大学。1987年8月27日。取得した28年4月2015。

- ^ Frank Newport、David W. Moore、およびLydia Saad(1999年12月13日)。「最も称賛される男性と女性:1948–1998」、ギャラップ組織。

- ^ a b フランクニューポート(1999年12月31日)。「マザーテレサは、世紀の最も称賛された人としてアメリカ人によって投票されました」、ギャラップ組織。

- ^ 世紀の最も大きいギャラップ/ CNN / USAトゥデイの投票。1999年12月20〜21日。

- ^ 「ノーベル委員会:1979年ノーベル平和賞プレスリリース」。

- ^ ロック、ミシェル(2007年3月22日)。「バークレーノーベル賞受賞者は賞金を慈善団体に寄付します[リンク切れ]」。サンフランシスコゲート。AP通信。2007年5月26日取得

- ^ マザーテレサ(1979年12月11日)。「ノーベル賞講演会」。NobelPrize.org。2007年5月25日取得。

- ^ 喫煙者1980年、11、28ページ

- ^ 「第4回女性会議へのマザーテレサのメッセージ」。EWTN。2006年10月6日。取得した3月28日に2016。

- ^ Larivée、Serge; キャロルセネシャル; GenevièveChénard(2013年3月1日)。「マザーテレサ:聖人以外の何でも...」モントリオール大学。2016年4月1日にオリジナルからアーカイブされました。取得した6年3月2013。

- ^ アドリアーナバートン(2013年3月5日)。「マザーテレサは 『聖人以外の何者でもなかった』、新しいカナダの研究は主張している」。グローブアンドメール。

- ^ 「「彼女がノーベル賞に値するとは思わない」– Anirudh Bhattacharyya – 2013年3月18日 "。

- ^ 「聖人と懐疑論者–ドラマイトラ– 2013年3月18日」。

- ^ ヒッチェンズ、クリストファー(2015年12月18日)。「愛と憎しみの伝説」。スレート。取得した19年12月2015。

- ^ ヒッチェンズ(1995)、p。41

- ^ cf. NS。ジェームズ・マーティン、SJ、ニューヨーク・レビュー・オブ・ブックスの手紙、1996年9月19日、マザー・テレサの防衛、 2014年2月2日アクセス

- ^ 「聖人をめぐる論争」(2003年10月19日)。CBSニュース。

- ^ a b ChristopherHitchensによる「LessthanMiraculous」、無料お問い合わせ24(2)、2004年2月/ 3月。

- ^ アダムテイラー(2015年12月18日)。「マザーテレサがまだ多くの批評家にとって聖人ではない理由」。ワシントンポスト。

- ^ 「同じページ–アミットチョウドリ– 2013年3月18日」。

- ^ 「疑念の都市:マザーテレサへのコルカタの不安な愛–ニューアメリカメディア」。2018年8月2日にオリジナルからアーカイブされました。取得した17年11月2015。

- ^ ヨハネパウロ2世(2003年10月20日)。「マザーテレサの列福のためにローマに来た巡礼者へのヨハネパウロ2世の演説」。Vatican.va 。2007年3月13日取得。

- ^ David Van Biema (23 August 2007). "Mother Teresa's Crisis of Faith". TIME. Archived from the original on 25 August 2007.

- ^ "Sermon – Some Doubted". Edgewoodpc.org. 19 June 2011. Archived from the original on 15 October 2011. Retrieved 28 August 2011.

- ^ a b New Book Reveals Mother Teresa's Struggle with Faith Beliefnet, AP 2007

- ^ "Hitchens Takes on Mother Teresa". Newsweek. 28 August 2007. Retrieved 11 December 2008.

- ^ "The dark night of 'a blessed soul'". The Baltimore Sun. Baltimore. 19 October 2003.

- ^ "Mother Teresa's Crisis of Faith". Sun Times. Archived from the original on 11 October 2007. Retrieved 26 August 2007.

- ^ Teresa, Mother; Kolodiejchuk, Brian (2007). Mother Teresa: Come Be My Light. New York: Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-52037-9.

- ^ Pope Benedict XVI (25 December 2005). Deus caritas est[dead link]. (PDF). Vatican City, pp.10. Retrieved 2 August 2007.

- ^ Mother Teresa (197). No Greater Love. New World Library. ISBN 978-1-57731-201-7. Retrieved 12 August 2007.

- ^ a b "Mother Teresa of Calcutta Pays Tribute to St. Francis of Assisi" on the American Catholic website. Retrieved 30 May 2007.

- ^ "St. Francis of Assisi on the Joy of Poverty and the Value of Dung". Christian History | Learn the History of Christianity & the Church. Retrieved 21 December 2016.

- ^ a b Brown, Mick (2 September 2016). "Did Mother Teresa really perform miracles?". The Telegraph. Telegraph Media Group. Retrieved 4 September 2016.

- ^ "Mother Teresa: The Road to Official Sainthood". www.americancatholic.org. Archived from the original on 14 October 2012. Retrieved 13 September 2012.

- ^ Orr, David (10 May. 2003). "Medicine cured 'miracle' woman – not Mother Teresa, say doctors". The Telegraph. Retrieved 30 May 2007.

- ^ "Her Legacy: Acceptance and Doubts of a Miracle", by David Rohde. The New York Times. 20 October 2003

- ^ a b "What's Mother Teresa Got to Do with It?". Time.com. 13 October 2002. Retrieved 4 September2016.

- ^ Edamaruku, Sanal. "Catholic Church manufactured an ovarian miracle for Mother Teresa". Church and State. Retrieved 19 November 2016.

- ^ "History of the Cause of Mother Teresa". Catholic Online. Retrieved 4 September 2016.

- ^ Lattin, Don (12 October 2003). "Living Saint: Mother Teresa's fast track to canonization". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 4 September 2016.

- ^ Shaw, Russell. (1 September 2005)."Attacking a Saint". Archived from the original on 26 May 2007. Retrieved 14 September 2006., Catholic Herald. Retrieved 1 May 2007.

- ^ "Vatican news release". Vatican.va. 19 October 2003. Retrieved 24 August 2010.

- ^ a b "Mother Teresa to become saint after Pope recognises 'miracle' – report". The Guardian. Agence France-Presse. 18 December 2015. Retrieved 18 December 2015.

- ^ a b Povoledo, Elisabetta (3 September 2016). "Mother Teresa Is Made a Saint by Pope Francis". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 4 September 2016.

- ^ a b "Mother Teresa declared saint by Pope Francis at Vatican ceremony – BBC News". BBC News. 4 September 2016. Retrieved 4 September 2016.

- ^ "Mother Teresa to be co-patron of Calcutta Archdiocese".

- ^ "Mother Teresa named co-patron of Calcutta archdiocese : News Headlines". www.catholicculture.org.

- ^ Online., Herald Malaysia. "Archbishop D'Souza: Mother Teresa will be the co-patron of Calcutta". Herald Malaysia Online.

- ^ "The Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Calcutta – India". www.archdioceseofcalcutta.in.

- ^ a b c "Vatican declares Mother Teresa a patron saint of Calcutta".

- ^ Petrit Collaku (26 May 2011). "Kosovo Muslims Resent New Mother Teresa Statue". Balkan Insight. Retrieved 16 December 2014.

- ^ "First cathedral for Mother Teresa is consecrated in Kosovo". 5 September 2017.

- ^ ":: Welcome To Mother Teresa Women's University ::".

- ^ "Mother Theresa Post Graduate And Research Institute of Health Sciences, Pondicherry". Mtihs.Pondicherry.gov.in. Archived from the original on 24 March 2019. Retrieved 28 August 2011.

- ^ "Activities: Children home". Sevalaya. Archived from the original on 1 November 2014.

- ^ "Memories of Mother Teresa". Hinduonnet.com. 26 August 2006. Archived from the original on 23 May 2011. Retrieved 22 October 2011.

- ^ "Touch the Poor ..." India-today.com. 15 September 1997. Archived from the original on 3 September 2010. Retrieved 24 August 2010.

- ^ Navin Chawla (11 April 2008). "Mission Possible". Indiatoday.digitaltoday.in. Retrieved 24 August 2010.

- ^ ""Mother Express" to be launched on Aug 26". IBN Live. 2 August 2010. Archived from the originalon 12 August 2011. Retrieved 5 August 2010.

- ^ "Centre could have done more for Mother Teresa: Karunanidhi". The Times of India. 4 December 2010. Archived from the original on 4 November 2012.

- ^ "Centenary Celebrations of Mother Teresa". The New Indian Express. 5 December 2010. Archived from the original on 23 February 2015. Retrieved 28 August 2011.

- ^ "Charity contributes to the promotion of dialogue, solidarity and mutual understanding among people". International Day of Charity: 5 September. United Nations.

- ^ "A Measure Of The Man | Outlook India Magazine". OutlookIndia. Retrieved 11 March 2020.

- ^ Muggeridge, Malcolm (1986). Something beautiful for God : Mother Teresa of Calcutta (1st Harper & Row pbk. ed.). New York: Harper & Row. ISBN 0-06-066043-0.

- ^ "Mother Teresa Dies". BBC.

- ^ "Seeker of Souls". Time. 24 June 2001. Archived from the original on 24 August 2010. Retrieved 4 May 2010.

- ^ "MOTHER OF THE CENTURY". filmsdivision.org.

- ^ "MOTHER TERESA". filmsdivision.org.

- ^ "Bible Ki Kahaniya - Noah's Ark". Navodaya Studio. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- ^ "Actress draws on convent experience for 'Teresa' role". Chicago Tribune.

- ^ Greydanus, Steven D. "Mother Teresa (2003) | Decent Films – SDG Reviews". Decent Films.

- ^ "CAMIE awards". 6 July 2007. Archived from the original on 6 July 2007. Retrieved 31 December2016.

- ^ Schager, Nick (4 December 2015). "Film Review: 'The Letters'". Variety. Retrieved 21 December 2016.

- ^ Battles of History, Epic Rap (22 September 2019). "Mother Teresa vs Sigmund Freud. Epic Rap Battles of History". Retrieved 5 November 2019.

Sources

- Alpion, Gezim. Mother Teresa: Saint or Celebrity?. London: Routledge Press, 2007. ISBN 0-415-39247-0

- Banerjee, Sumanta (2004), "Revisiting Kolkata as an 'NRB' [non-resident Bengali]", Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 39, No. 49 ( 4–10 Dec 2004), pp. 5203–5205

- Benenate, Becky and Joseph Durepos (eds). Mother Teresa: No Greater Love (Fine Communications, 2000) ISBN 1-56731-401-5

- Bindra, Satinder (7 September 2001). "Archbishop: Mother Teresa underwent exorcism". CNN.com World. Archived from the original on 17 December 2006. Retrieved 23 October 2006.

- Chatterjee, Aroup. Mother Teresa: The Final Verdict (Meteor Books, 2003). ISBN 81-88248-00-2, introduction and first three chapters of fourteen (without pictures). Critical examination of Agnes Bojaxhiu's life and work.

- Chawla, Navin. Mother Teresa. Rockport, Mass: Element Books, 1996. ISBN 1-85230-911-3

- Chawla, Navin. Mother Teresa: The Authorized Biography. Diane Pub Co. (March 1992). ISBN 978-0-7567-5548-5. First published by Sinclair-Stevenson, UK (1992), since translated into 14 languages in India and abroad. Indian language editions include Hindi, Bengali, Gujarati, Malayalam, Tamil, Telugu, and Kannada. The foreign language editions include French, German, Dutch, Spanish, Italian, Polish, Japanese, and Thai. In both Indian and foreign languages, there have been multiple editions. The bulk of royalty income goes to charity.

- Chawla, Navin. The miracle of faith, article in the Hindu dated 25 August 2007 "The miracle of faith"

- Chawla, Navin. Touch the Poor ... – article in India Today dated 15 September 1997 " Touch the Poor ..."

- Chawla, Navin. The path to Sainthood, article in The Hindu dated Saturday, 4 October 2003 " The path to Sainthood "

- Chawla, Navin. In the shadow of a saint, article in The Indian Express dated 5 September 2007 " In the shadow of a saint "

- Chawla, Navin. Mother Teresa and the joy of giving, article in The Hindu dated 26 August 2008 " Mother Teresa and the joy of giving"

- Clark, David, (2002), "Between Hope And Acceptance: The Medicalisation Of Dying", British Medical Journal, Vol. 324, No. 7342 (13 April 2002), pp. 905–907

- Clucas, Joan. Mother Teresa. New York: Chelsea House, 1988. ISBN 1-55546-855-1

- Dwivedi, Brijal. Mother Teresa: Woman of the Century

- Egan, Eileen and Kathleen Egan, OSB. Prayertimes with Mother Teresa: A New Adventure in Prayer, Doubleday, 1989. ISBN 978-0-385-26231-6.

- Greene, Meg. Mother Teresa: A Biography, Greenwood Press, 2004. ISBN 0-313-32771-8

- Hitchens, Christopher (1995). The Missionary Position: Mother Teresa in Theory and Practice. London: Verso. ISBN 978-1-85984-054-2.

- Hitchens, Christopher (20 October 2003). "Mommie Dearest". Slate. Archived from the original on 13 August 2014. Retrieved 5 September 2014.

- Kwilecki、Susan、Loretta S. Wilson、「マザーテレサは彼女の効用を最大化したか?合理的選択理論のイディオグラフィックアプリケーション」、Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion、Vol。37、No。2(1998年6月)、205〜221ページ

- (フランス語で) Larivée、セルジュ(モントリオール大学)、キャロルSénéchal(オタワ大学)、およびジュヌヴィエーヴChénard(モントリオール大学)。「LescôtésténébreuxdeMèreTeresa」宗教/科学宗教学の研究。2013年9月vol。42号 3、p。319〜345。印刷前にオンラインで公開2013年1月15日、doi:10.1177 / 0008429812469894。利用可能なSAGEジャーナル。

- ルジョリー、エドワード。カルカッタのマザーテレサ。サンフランシスコ:ハーパー&ロウ、1983年ISBN 0-06-065217-9 。

- Livermore、Colette、Hope Endures:Mother Teresaを離れ、信仰を失い、意味を探します。フリープレス(2008)ISBN 1-4165-9361-6 。

- Macpherson、C。(2009)「痛みの治療不足は倫理原則に違反している」、Journal of Medical Ethics、Vol。35、No。10(2009年10月)、603〜606ページ

- マッカーシー、コールマン、ワシントンポスト、1997年9月6日、ノーベル賞受賞者が最貧層を支援、2014年2月2日にアクセス

- Mehta&Veerendra Raj&Vimla、マザーテレサインスピレーションインシデント、出版部門、I&B省、政府。インド、2004年、ISBN 81-230-1167-9 。

- マゲリッジ、マルコム。神にとって美しい何か。ロンドン:コリンズ、1971年ISBN 0-06-066043-0。

- Muntaykkal、TT祝福されたマザーテレサ:あなたの心への彼女の旅。ISBN 1-903650-61-5。ISBN 0-7648-1110-X。「書評」。2006年2月9日にオリジナルからアーカイブされました。 。

- Panke、Joan T.(2002)、「Not a Sad Place」、The American Journal of Nursing、Vol。102、No。9(2002年9月)、p。13

- ラグーライとナヴィンチャウラ。信仰と思いやり:マザーテレサの生涯と仕事。Element Books Ltd.(1996年12月)。ISBN 978-1-85230-912-1。オランダ語とスペイン語にも翻訳されています。

- Rajagopal MR、Joranson DE、およびGilson AM(2001)、「インドにおけるオピオイドの医療使用、誤用、および流用」、The Lancet、Vol。358、2001年7月14日、139〜143ページ

- Rajagopal MR、およびJoranson DE(2007)、「インド:オピオイドの入手可能性–最新情報」、The Journal of Pain Symptom Management、Vol。33:615–622。

- ラヤゴパルMR(2011)、国連薬物犯罪事務所へのインタビュー、2011年4月 インド:緩和ケアのためにオピオイドを利用できるようにするためのバランスの原則

- スコット、デビッド。愛の革命:マザーテレサの意味。シカゴ:ロヨラプレス、2005年ISBN 0-8294-2031-2。

- アンセバ、アン。マザーテレサ:イメージを超えて。ニューヨーク:ダブルデイ、1997 ISBN 0-385-48952-8。

- ルイーズ、スラビセク。マザーテレサ。ニューヨーク:Infobase出版、2007年ISBN 0-7910-9433-2。

- 喫煙者、バーバラ(1980年2月1日)。「マザーテレサ–聖なる牛?」。フリーシンカー。2014年9月5日にオリジナルからアーカイブされました。検索された5年9月2014。

- スピンク、キャスリン。マザーテレサ:完全な公認伝記。ニューヨーク:ハーパーコリンズ、1997年ISBN 0-06-250825-3

- テレサ、マザー他、マザーテレサ:私自身の言葉で。グラマシーブックス、1997年ISBN 0-517-20169-0。

- テレサ、マザー、マザーテレサ:「カルカッタの聖」のプライベート・著作:私の光で来てダブルデイ、2007:ブライアン・コロディエージャック、ニューヨークによる解説で編集し、ISBN 0-385-52037-9。

- ウィリアムズ、ポール。マザーテレサ。インディアナポリス:アルファブックス、2002年ISBN 0-02-864278-3。

- Wüllenweber、ウォルター。「Nehmenistseliger denngeben。MutterTeresa—wo sind ihre Millionen?」Stern(毎週ドイツ語で示されている)、1998年9月10日。英語の翻訳。

外部リンク

| ウィキメディアコモンズには、マザーテレサに関連するメディアがあります。 |

| ウィキクォートには、マザーテレサに関連する引用があります。 |

- 公式サイト

- マザー・テレサの記念で永遠のWordのテレビネットワーク(EWTN)

- ギャラリー付きマザーテレサ記念館 (ロシア語)

- Nobelprize.orgのマザーテレサ

- 「マザーテレサはニュースと解説を集めました」。ニューヨークタイムズ。

- 外観上のC-SPAN

- マザー・テレサのチャリティー父の宣教師

- 「あなたがすることは何でも...」 全国祈りの朝食でのスピーチ。ワシントンDC:Priests forLife。1994年2月3日。

- ヌーナン、ペギー(1998年2月)。「それでも、小さな声」。危機。16(2):12–17。

マザーテレサは、1994年の全国祈りの朝食の演説で、優れたスピーチの書き方のほとんどすべてのルールを破りましたが、非常に強力で非常に記憶に残るスピーチを行いました。

- パレンティ、マイケル(2007年10月22日)。「マザーテレサ、ヨハネパウロ2世、そしてファストトラックセインツ」。コモンドリームズ。

- マザーテレサは対照的です:

- Van Biema、David(2007年8月23日)。「マザーテレサの信仰の危機」。時間。

イエスはあなたをとても特別に愛しておられます。[しかし]私に関しては—沈黙と空虚はとても大きい—私は見たり見たりしない—聞いたり聞いたりしない。

- 「姉妹から母へそして聖人へ:マザーテレサの旅」。ニュースカルナータカ。2016年8月31日。

血で、私はアルバニア人です。市民権によって、インド人。信仰によって、私はカトリックの修道女です。私の召しに関しては、私は世界に属しています。私の心に関しては、私は完全にイエスの心に属しています。

- Van Biema、David(2007年8月23日)。「マザーテレサの信仰の危機」。時間。

- マザー・テレサ

- 1910年の誕生

- 1997年の死亡

- 20世紀のインドの女性

- 20世紀のインド人

- アルバニアのローマカトリック聖人

- 北マケドニアのアルバニア人

- 教皇ヨハネパウロ2世による列福

- 教皇フランシスコによる列聖

- 近代後期のキリスト教の女性聖人

- 議会の金メダル受賞者

- 神格化された人々

- インドにおける疾病関連の死亡

- 女性のローマカトリック宣教師

- カトリックの宗教コミュニティの創設者

- オーストラリア勲章の名誉会員

- メリット勲章の名誉会員

- インドのノーベル賞受賞者

- インドの平和主義者

- アルバニア系のインド人

- インドのローマカトリック聖人

- インドのローマカトリックの宗教的な姉妹と修道女

- インドの女性慈善家

- インドの慈善家

- ソーシャルワーカー

- ノーベル平和賞受賞者

- ダージリンの人々

- コルカタの人々

- スコピエの人々

- インドの市民権を取得した人

- 大統領自由勲章の受賞者

- マグサイサイ賞受賞者

- バーラト・ラトナの受信者

- ソーシャルワークにおけるパドマシュリ勲章の受領者

- 地域のヒンドゥー教の女神

- インドのローマカトリック宣教師

- 上司一般

- テンプルトン賞受賞者

- 教皇ヨハネパウロ2世による崇拝されたカトリック教徒

- 女性の人道主義者

- 女性ノーベル賞受賞者

- インドへのユーゴスラビア移民

- インドの国葬

- 西ベンガルのソーシャルワーカー

- アルバニアのローマカトリックの宗教的な姉妹と修道女

コメント

コメントを投稿