太陽系は約46億年前、銀河系(天の川銀河)の中心から約26,000光年離れた、オリオン腕の中に位置。

ヒンドゥー教

| 上のシリーズの一部 |

| ヒンドゥー教 |

|---|

|

ヒンドゥー教( / ˈhɪnduɪzəm / ) [ 1 ]は、インドの宗教とダルマ、または生き方です。[注1] [注2]これは世界で3番目に大きい宗教であり、12億人を超える信者、つまりヒンズー教徒として知られる世界人口の15〜16%を占めています。[2] [web 1] [web 2]ヒンドゥーという言葉は異名であり、[3] [4] [注3]ヒンドゥー教は世界で最も古い宗教と呼ばれていますが、[注4]多くの開業医は、自分たちの宗教をサナータニーダルマ(サンスクリット: सनातनधर्म、 lit。 「永遠のダルマ」)と呼んでいます。[5] [6] [7] [8] [注5]もう1つ、あまり適切ではありませんが、 [9]自己指定はVaidikaダルマ、 [10] [11] [12] [13] 'ダルマに関連するヴェーダ。」[14]

ヒンドゥー教は、さまざまな哲学と共有された概念、儀式、宇宙システム、巡礼地、そして神学、形而上学、神話、ヴェーダのヤグナ、ヨガ、アガミックな儀式、寺院の建設について議論する共有されたテキストソースによって特徴づけられる多様な思考システムです。他のトピック。[15]ヒンドゥー教の信仰における著名なテーマには、4つのプルシャールタ、人間の生活の適切な目標または目的が含まれます。すなわち、ダルマ(倫理/義務)、アルタ(繁栄/仕事)、カマ(欲望/情熱)とモクシャ(情熱と死と再生のサイクルからの解放/自由)、[16] [17]、そしてカルマ(行動、意図と結果)とsaṃsāra(死と再生のサイクル)。[18] [19]ヒンドゥー教は、正直、生き物を傷つけないこと(アヒンサー)、忍耐、忍耐、自制心、美徳、思いやりなどの永遠の義務を規定しています。[web 3] [20]ヒンドゥー教の慣習には、プージャ(崇拝)や朗読、ジャパ、瞑想(ディヤーナ)などの儀式が含まれます。)、家族向けの通過儀礼、毎年恒例の祭り、時折の巡礼。さまざまなヨガの練習に加えて、一部のヒンズー教徒は、モクシャを達成するために、社会的世界と物質的な所有物を離れ、生涯のサンニャーサ(出家生活)に従事します。[21]

ヒンドゥー教のテキストは、シュルティ(「聞いた」)とスムリティ(「覚えている」)に分類され、その主要な経典は、ヴェーダ、ウパニシャッド、プラーナ、マハーバーラタ、ラーマーヤナ、およびガマです。[18] [22]ヒンドゥー哲学の6つのアースティカ派があり、ヴェーダーンタ派、すなわちサーンキヤ学派、ヨガ学派、ニヤーヤ学派、ヴァイシェーシカ派、ミーマーンサー学派、ヴェーダーンタ派を認めています。[23] [24][25]プラーナの年代学はヴェーダのリシから始まって数千年の系譜を示しているが、学者はヒンドゥー教をバラモンの正統性[注8]とさまざまなインド人との融合[注6]または統合[26] [注7]と文化、 [27] [注9]多様なルーツ[28] [注10]を持ち、特定の創設者はいない。[29]このヒンドゥー教の統合は、ヴェーダ時代の後、c。500 [30] –200 [31] BCEおよびc。西暦300年、[ 30]叙事詩と最初のプラーナが構成された、第二の都市化とヒンドゥー教の初期の古典派。[30] [31]それは中世に繁栄し、インドの仏教は衰退した。[32]

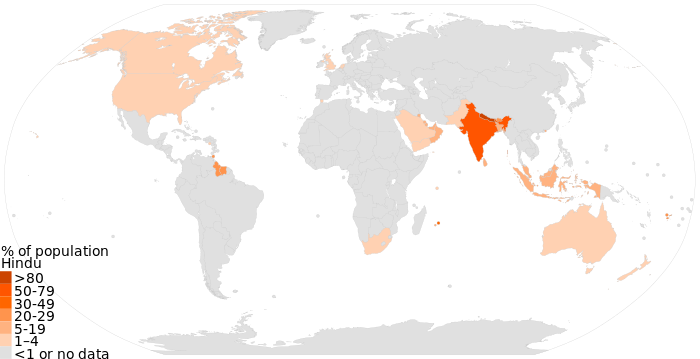

現在、ヒンドゥー教の4つの主要な宗派は、 Vaishnavism、Shaivism、Shaktism、および Smartaの伝統です。[33] [34] [35] [36]ヒンドゥー教のテキストにおける権威と永遠の真実の源泉は重要な役割を果たしますが、これらの真実の理解を深め、さらに進めるために権威を問うというヒンドゥー教の強い伝統もあります。伝統を発展させる。[37]ヒンドゥー教は、インド、ネパール、モーリシャスで最も広く公言されている信仰です。東南アジアにはかなりの数のヒンズー教徒のコミュニティがありますバリ、インドネシア、[38]カリブ海、北アメリカ、ヨーロッパ、オセアニア、アフリカ、およびその他の地域を含む。[39] [40]

語源

ヒンドゥーという言葉は、インド・アーリア人[41] /サンスクリット語[42]のルートシンドゥに由来しています。[42] [43] Asko Parpolaによると、イラン祖語の音変化* s > hは、西暦前850年から600年の間に発生しました。[44]

実践と信念のコレクションを説明するために英語の用語「ヒンドゥー教」を使用することは、かなり最近の解釈です。これは、1816年から17年にラジャラムモハンロイによって最初に使用されました。[45]「ヒンドゥー教」という用語は、1830年頃に、イギリスの植民地主義に反対し、他の宗教団体との差別化を望んでいたインディアンによって造られました。[45] [46] [47]イギリス人がコミュニティを宗教によって厳密に分類し始める前は、インド人は一般的に彼らの宗教的信念だけで自分たちを定義していませんでした。代わりに、アイデンティティは、地域、言語、 varṇa、jāti、職業、および宗派に基づいて大部分がセグメント化されました。[48] [注11]18世紀になると、ヨーロッパの商人や入植者は、インドの宗教の信者をまとめてヒンドゥー教徒と呼び始めました。[49]

「ヒンドゥー」という言葉はずっと古く、インド亜大陸の北西部にあるインダス川の名前として使われたと考えられています。[45] [42] [note 12] Gavin Floodによると、「ヒンドゥーという実際の用語は、インダス川(サンスクリット語:シンドゥ)の向こうに住んでいた人々のペルシア語の地理的用語として最初に出現します」 [42]。ダレイオス1世(紀元前550〜486年)の紀元前6世紀の碑文。[51]これらの古代の記録におけるヒンドゥーという用語は地理的な用語であり、宗教を指すものではありませんでした。[42]宗教を暗示する「ヒンドゥー」の最も初期の既知の記録の中には、玄奘による7世紀のCE中国語テキスト「西部地域の記録」[51]および「アブドゥルマリクイサミによる14世紀のペルシャテキストFutuhu's -salatin 」があります。 。[注3]

タパーは、ヒンドゥーという言葉がアヴェスターでヘプタヒンドゥとして発見されたと述べています。これはリグヴェーダのサプタシンドゥに相当します。一方、hndstn(ヒンドゥスターンと発音)は、南アジア北西部の一部を指す3世紀のサーサーン朝の碑文にあります。[52]アラビア語のアル・ハインドは、インダス川の向こうに住む人々を指していました。[53]このアラビア語は、それ自体がイスラム以前のペルシア語であるヒンドゥー教から取られたものであり、これはすべてのインド人を指します。13世紀までに、ヒンドゥスタンは人気のある代替品として登場しました「ヒンズー教の地」を意味するインドの名前。[54] [注13]

ヒンドゥーという用語は、後にカシミールのラジャタランギニス(ヒンドゥーカ、1450年頃)などのサンスクリット語のテキストや、ChaitanyaCharitamritaやChaitanyaBhagavataなどの16〜18世紀のベンガル語GaudiyaVaishnavaのテキストで時折使用されました。これらのテキストは、ヒンズー教徒とヤヴァナ(外国人)またはムレッチャ(野蛮人)と呼ばれるイスラム教徒を区別するために使用され、16世紀のチャイタンヤチャリタムリタのテキストと17世紀のバクタマラのテキストは「ヒンズー教のダルマ」というフレーズを使用しています。[56] ヨーロッパの商人や入植者がインドの宗教の信者をまとめてヒンドゥー教徒と呼び始めたのは18世紀の終わりごろでした。【注14】

ヒンドゥー教という用語は、18世紀に英語に導入され、インドに固有の宗教的、哲学的、文化的伝統を表しています。[60]

定義

ヒンドゥー教には、精神性と伝統に関する多様な考えが含まれていますが、教会論的秩序、疑う余地のない宗教的権威、統治体、預言者、拘束力のある聖典はありません。ヒンズー教徒は、多神教、汎神論、万有内在神論、汎神論、単一神教、一神教、一元論、不可知論的、無神論的、またはヒューマニストになることを選択できます。[61] [62] [63]ドニガーによれば、「信仰とライフスタイルのすべての主要な問題についての考え-菜食主義、非暴力、再生への信念、さらにはカースト–教義ではなく、議論の対象です。」[48]

ヒンドゥー教という用語に含まれる幅広い伝統や考えのために、包括的な定義に到達することは困難です。[42]宗教は、「それを定義し、分類したいという私たちの願望に逆らいます」。[64]ヒンドゥー教は、宗教、宗教的伝統、一連の宗教的信念、および「生き方」としてさまざまに定義されてきました。[65] [注1]西洋の語彙の観点から、他の信仰のようなヒンドゥー教は適切に宗教と呼ばれています。インドでは、ダルマという用語が好まれます。これは、西洋の用語である宗教よりも広い意味を持ちます。[66]

インドとその文化と宗教の研究、および「ヒンドゥー教」の定義は、植民地主義の利益と西洋の宗教の概念によって形作られてきました。[67] [68] 1990年代以降、これらの影響とその結果は、ヒンドゥー教の学者の間で議論の的となっている[67] [注15]。また、インドに対する西洋の見方の批評家にも引き継がれている。[69] [注16]

タイポロジー

一般的に知られているヒンドゥー教は、いくつかの主要な流れに細分することができます。6つのダルサナ(哲学)への歴史的な分割の中で、ヴェーダーンタ派とヨガの2つの学校が現在最も有名です。[23]一次神によって分類される、4つの主要なヒンドゥー教の現代の流れは、シヴァ派(シヴァ)、ヴィシュヌ派(ヴィシュヌ)、シャクティ派(デヴィ)、スマールタ派(5つの神が平等に扱われる)です。[33] [34] [35] [36]ヒンドゥー教はまた、多くの神の存在を受け入れます。多くのヒンドゥー教徒は、神々を単一の非人格的な絶対的または究極の現実または神の側面または顕現と見なしますが、一部のヒンドゥー教徒は、特定の神が最高を表し、さまざまな神がこの最高のより低い顕現であると主張します。[70]他の注目すべき特徴には、アートマン(自己)の存在への信念、アートマンの生まれ変わり、カルマ、そしてダルマへの信念(義務、権利、法律、行動、美徳、正しい生き方)が含まれます。

McDaniel(2007)は、ヒンドゥー教徒の間の感情の表現を理解するために、ヒンドゥー教を6つの主要な種類と多数のマイナーな種類に分類しています。[71]マクダニエルによれば、主要な種類は、地元の伝統と地元の神々のカルトに基づく民俗ヒンドゥー教であり、最も古く、非識字のシステムである。紀元前2千年紀に追跡可能なヴェーダの最も初期の層に基づくヴェーダのヒンドゥー教。知識と知恵を強調する、AdvaitaVedantaを含むウパニシャッドの哲学に基づくヴェーダーンタ派のヒンドゥー教。パタンジャリのヨガスートラのテキストに従ったヨガのヒンドゥー教内省的な意識を強調する。マクダニエルが述べているダーミックヒンドゥー教または「日常の道徳」は、「カルマ、牛、カーストを信じる唯一のヒンドゥー教の宗教」として定型化されている本もあります。そしてバクティまたは献身的なヒンドゥー教。ここでは、激しい感情が精神的な追求に精巧に組み込まれています。[71]

マイケルズは、3つのヒンドゥー教と4つの形態のヒンドゥー教を区別しています。[72]ヒンドゥー教の3つの宗教は、「バラモン・サンスクリットのヒンドゥー教」、「民間信仰と部族の宗教」、「創設された宗教」である。[73]ヒンドゥー教の4つの形態は、古典的な「カルマ・マルガ」、[74] ジュニャーナ・マルガ、[75] バクティ・マルガ、[75] 、そして軍国主義の伝統に根ざした「英雄主義」です。これらの軍事的伝統には、ラーマ主義(叙事詩の英雄ラーマの崇拝、彼がヴィシュヌの化身であると信じている)[76]および政治的ヒンドゥー教の一部が含まれます。 「ヒロイズム」はvirya-margaとも呼ばれます。[75]マイケルズによれば、ヒンドゥー教徒の9人に1人は、実践的か非実践的かを問わず、バラモン教-サンスクリット教のヒンドゥー教と民間信仰の類型学の一方または両方に出生によって属している。彼はほとんどのヒンズー教徒を、モクシャに焦点を当て、しばしばバラモン教の司祭の権威を強調しないが、バラモン・サンスクリットのヒンドゥー教の儀式の文法を組み込んだ、ヴィシュヌ派やシヴァ派などの「創設された宗教」の1つに属するものとして分類しています。[77]彼は「創設された宗教」の中に仏教、ジャイナ教、現在は別個の宗教であるシーク教、ブラフモ・サマージや神智学協会などのシンクレティズム運動を含んでいる。、マハリシ・マヘシュ・ヨギやISKCONなどのさまざまな「教祖主義」や新宗教運動も同様です。[78]

インデンは、ヒンドゥー教を類型学で分類する試みは、改宗宣教師と植民地当局者が彼らの利益からヒンドゥー教を理解し描写しようとした帝国時代に始まったと述べています。[79]ヒンドゥー教は、精神の理由からではなく、幻想と創造的な想像力、概念的ではなく象徴的、倫理的ではなく感情的、合理的または精神的ではなく、認知的神秘主義から発していると解釈された。このステレオタイプは、植民地プロジェクトの道徳的正当性を提供する、時代の帝国の命令とともに、インデンに続いて適合したと述べています。[79]部族のアニミズムから仏教まで、すべてがヒンドゥー教の一部として包含されていました。初期の報告は、ヒンドゥー教の類型学の伝統と学問的前提、ならびにインド学の基礎にあった主要な仮定と欠陥のある前提を設定しました。インデンによれば、ヒンドゥー教は、帝国の宗教家がそれをステレオタイプ化したものではなく、ヒンドゥー教を単に不二一元論の汎神論と哲学的理想主義と同一視することも適切ではありません。[79]

ヒンドゥー教の見解

サナータニーダルマ

その信奉者にとって、ヒンドゥー教は伝統的な生き方です。[80]多くの開業医は、ヒンドゥー教の「正統な」形式をサナタナ・ダルマ、「永遠の法」または「永遠の道」と呼んでいます。[81] [82]ヒンズー教徒は、ヒンズー教を数千年前のものと見なしている。マハバラタ、ラーマーヤナ、プラーナで語られている古代インドの歴史における出来事の時系列であるプラーナ年代学は、紀元前3000年よりかなり前に始まるヒンドゥー教に関連する出来事の年代学を想定しています。サンスクリット語のダルマは、宗教よりもはるかに広い意味を持っています同等ではありません。ヒンズー教の生活のすべての側面、すなわち富の獲得(アルタ)、欲望の実現(カーマ)、解放の達成(モクシャ)は、「正しい生き方」と永遠の調和の原則をその実現にカプセル化するダルマの一部です。[83] [84]

ブリタニカ百科事典の編集者によると、サナタナダルマは歴史的に、ヒンドゥー教で宗教的に定められた「永遠の」義務、正直、生き物を傷つけることを控える(ahiṃsā)、純粋さ、善意、慈悲、忍耐、寛容、自制などの義務に言及していました。抑制、寛大さ、そして禁欲主義。これらの義務は、ヒンドゥー教の階級、カースト、宗派に関係なく適用され、階級やカースト(varṇa)や人生の段階(puruṣārtha)に応じて、「自分の義務」であるsvadharmaとは対照的でした。[ウェブ3]近年、この用語は、ヒンドゥー教の指導者、改革者、民族主義者によってヒンドゥー教を指すために使用されています。サナタナダルマは、歴史を超越し、「不変で、不可分で、最終的には無宗派」である、ヒンドゥー教の「永遠の」真実と教えの同義語になりました。[ウェブ3]

キム・ノットやブライアン・ハッチャーなどの他の学者によると、サナタナ・ダルマは「時代を超越した永遠の真実のセット」を指し、これがヒンズー教徒が彼らの宗教の起源をどのように見ているかです。それは、人類の歴史を超えた起源を持つ永遠の真理と伝統と見なされており、世界で最も古い経典であるヴェーダで神聖に明らかにされた真理(シュルティ)です。[6] [85]多くのヒンズー教徒にとって、「教義と単一の創設者にたどることができる制度」を意味する範囲での西洋の用語「宗教」は彼らの伝統には不適切である、とハッチャーは述べている。彼らにとって、ヒンドゥー教は少なくとも古代ヴェーダ時代にまでさかのぼることができる伝統です。[6] [86] [注17]

ヴァイディカダルマ

ヒンドゥー教をヴァイディカダルマと呼ぶ人もいます。[10]サンスクリット語の「Vaidika」という言葉は、「ヴェーダに由来するか、それに準拠する」または「ヴェーダに関連する」を意味します。[web 4]伝統的な学者は、さまざまなインドの学校をジャイナ教、仏教、順世派と区別するために、ヴェーダを権威ある知識の源として受け入れる人と受け入れない人であるヴァイディカとアヴァイディカという用語を使用しました。クラウス・クロスターマイアーによれば、ヴァイディカ・ダルマという用語は、ヒンドゥー教の最も初期の自己指定です。[11] [12] Arvind Sharmaによると、歴史的証拠は、「ヒンズー教徒は彼らの宗教をvaidikadharmaという用語で呼んでいたことを示唆している。[13]ブライアン・K・スミスによれば、「ヴァイディカ・ダルマという用語が歴史に適切な譲歩をもってできないかどうかについては、「少なくとも議論の余地がある」。、文化的、およびイデオロギー的特異性は、「ヒンドゥー教」または「ヒンドゥー教」に匹敵し、翻訳されます。」[9]

アレクシスサンダーソンによると、初期のサンスクリット語のテキストは、ヴァイディカ、ヴァイシュナヴァ、シャイバ、シャクタ、サウラ、仏教、ジャイナの伝統を区別しています。しかし、1千年紀後期のインドのコンセンサスは、「確かに、仏教やジャイナ教とは対照的に、ヒンドゥー教に対応する複雑な実体を概念化するようになりました」。[web 5]ヒンドゥー哲学のミーマーンサー学派の中には、ヴェーダに準拠していなかったため、パンカラトリカなどのアガマを無効と見なした人もいました。一部のカシミールの学者は、秘教のタントラの伝統がヴァイディカダルマの一部であることを拒否しました。[ウェブ5] [ウェブ6]西暦500年頃までのデータが可能なアティマルガシヴァ派の禁欲主義の伝統は、ヴァイディカの枠組みに異議を唱え、彼らのアガマと慣習は有効であるだけでなく、ヴァイディカのものよりも優れていると主張しました。[web 7]しかし、サンダーソンは付け加えます。このシヴァ派の禁欲主義の伝統は、ヴェーダの伝統に真に忠実であると見なし、「バラモン教のシュルティとスムリティは、彼ら自身の領域で普遍的かつ独自に有効であると満場一致で保持しました。それ自体、彼ら[ヴェーダ]は人間の唯一の有効な知識の手段である[...]」。[ウェブ7]

ヴァイディカダルマという用語は「ヴェーダに基づく」実践規範を意味しますが、「ヴェーダに基づく」が実際に何を意味するのかは不明です、とジュリアスリプナーは述べています。[86]ヴァイディカ・ダルマまたは「ヴェーダの生き方」は、「ヒンドゥー教は必ずしも宗教的である」という意味ではなく、ヒンドゥー教徒がその用語に対して普遍的に受け入れられている「慣習的または制度的意味」を持っているという意味ではない。[86]多くの人にとって、それは文化的な用語です。多くのヒンズー教徒はヴェーダのコピーを持っておらず、キリスト教徒のようにヴェーダの一部を見たり、個人的に読んだりしたことはありません。それでも、リプナーは、「これは、彼らの[ヒンドゥー教徒]の生涯を意味するものではありません」と述べています。

多くの宗教的なヒンズー教徒は暗黙のうちにヴェーダの権威を認めていますが、この承認はしばしば「誰かが自分自身をヒンズー教徒と見なしているという宣言にすぎません」[88] [注18]そして「今日のほとんどのインド人はヴェーダであり、テキストの内容を考慮していません。」[89]一部のヒンズー教徒はヴェーダの権威に異議を唱え、それによってヒンズー教の歴史に対するその重要性を暗黙のうちに認めている、とリプナーは述べている。[86]

ヒンドゥー教のモダニズム

19世紀以降、インドのモダニストはヒンドゥー教をインド文明の主要な資産として再主張し[68] 、その一方でヒンドゥー教をタントラの要素から「浄化」し[92]、ヴェーダの要素を高めました。西洋の固定観念は逆転し、普遍的な側面を強調し、社会問題の現代的なアプローチを導入しました。[68]このアプローチは、インドだけでなく西側でも大きな魅力を持っていた。[68]「ヒンドゥーモダニズム」[93]の主な代表者は、ラジャラムモハンロイ、ヴィヴェーカーナンダ、サルヴパッリーラーダクリシュナン、マハトマガンディーです。[94] ラジャ・ラムモハン・ロイは、ヒンドゥー・ルネッサンスの父として知られています。[95]彼はスワミ・ヴィヴェーカーナンダ(1863–1902)に大きな影響を与えた。彼は洪水によれば、「現代のヒンドゥー教の自己理解の発展と西洋のヒンドゥー教観の形成において非常に重要な人物」であった。[96]彼の哲学の中心は、神はすべての存在に存在し、すべての人間はこの「生来の神」との結合を達成できるという考えであり[93]、この神を他の人の本質として見ることはさらに愛し、社会的になるという考えです調和。[93]ヴィヴェーカーナンダによれば、ヒンドゥー教には本質的な統一があり、それはその多くの形態の多様性の根底にある。[93]洪水によると、ヴィヴェーカーナンダのヒンドゥー教のビジョンは、「今日、ほとんどの英語を話す中流階級のヒンドゥー教徒に一般的に受け入れられているものです」。[97] Sarvepalli Radhakrishnanは、西洋の合理主義とヒンドゥー教を調和させようとし、「ヒンドゥー教を本質的に合理的で人道的な宗教的経験として提示した」。[98]

この「グローバルヒンドゥー教」[99]は、国境を越えて[99] 、ヒンドゥー教のディアスポラコミュニティと西洋人の両方にとって「キリスト教、イスラム教、仏教と並んで世界の宗教になる」[99]という世界的な魅力を持っています。非西洋の文化や宗教に惹かれる人たち。[99]それは、社会正義、平和、そして「人類の精神的変容」などの普遍的な精神的価値を強調している。[99]それは部分的に「再培養」[100]またはピザ効果[100]のために開発されました。ヒンドゥー教の文化の要素が西洋に輸出され、そこで人気を博し、その結果、インドでも人気を博しました。[100]このヒンドゥー教文化のグローバル化は、「西洋社会において重要な文化的勢力となり、その起源であるインドにおいて重要な文化的勢力となった教えを西洋にもたらした」。[101]

法的定義

インド法におけるヒンドゥー教の定義は、「敬意を持ってヴェーダを受け入れること、モクシャへの手段や方法が多様であるという事実の認識、そして崇拝される神の数が多いという真実の実現」です。[102] [103]

学術的見解

ヒンドゥー教という用語は、18世紀の西洋民族誌で造られ[60] [注19]、さまざまなインドの文化と伝統の融合[注6]または統合[注7] [26]を指します[27] [注9]多様なルーツを持ち[28] [注10]、創設者はいない。[29]このヒンドゥー教の統合は、ヴェーダ時代の後、c。500 [30] –200 [31] BCEおよびc。西暦300年、[30]第二次都市化の時代とヒンドゥー教の初期の古典派時代、叙事詩そして最初のプラーナが作曲されました。[30] [31]それは中世に繁栄し、インドの仏教は衰退した。[32]信念の変化に対するヒンドゥー教の寛容とその幅広い伝統は、伝統的な西洋の概念に従って宗教として定義することを困難にしている。[104]

一部の学者は、ヒンドゥー教は明確に定義された厳格な実体としてではなく、「曖昧なエッジ」を持つカテゴリーと見なすことができると示唆しています。宗教的表現のいくつかの形式はヒンドゥー教の中心であり、他の形式は中心的ではありませんが、依然としてカテゴリー内にあります。この考えに基づいて、ガブリエラ・アイヒンガー・フェロ・ルッツィは、ヒンドゥー教の定義に対する「プロトタイプ理論アプローチ」を開発しました。[105]

多様性と団結

多様性

ヒンドゥー教の信念は広大で多様であるため、ヒンドゥー教は単一の宗教ではなく、宗教の家族と呼ばれることがよくあります。[web 9]この宗教ファミリーの各宗教には、さまざまな神学、実践、および聖典があります。[web 10] [106] [107] [108] [web 11]ヒンドゥー教には、「信仰または信条の宣言にコード化された統一された信条体系」 [ 42]はなく、むしろ複数を含む総称です。インドの宗教的現象の。[109] [110]インドの最高裁判所によると、

ヒンドゥー教という用語の単一の定義に関する問題の一部は、ヒンドゥー教には創設者がいないという事実です。[112]それは様々な伝統、[113]「バラモンの正統性、放棄者の伝統、そして人気のあるまたは地元の伝統」の統合です。[114]

一部のヒンドゥー哲学は創造の有神論的存在論を仮定しているが、他のヒンドゥー教徒は無神論者であるか、または無神論者であったため、有神論をヒンドゥー教の統一教義として使用することも難しい。[115]

一体感

違いはありますが、一体感もあります。[116]例外はあるものの、ほとんどのヒンドゥー教の伝統は、一連の宗教的または神聖な文学、ヴェーダ[117]を崇拝している。[118]これらのテキストは、ヒンズー教徒の古代文化遺産と誇りを思い起こさせるものです[119] [120]ルイ・レノウは、「最も正統な領域でさえ、ヴェーダへの敬意は単純なものになっています。帽子を上げる」。[119] [121]

ハルブファスは、シヴァ派とヴィシュヌ派は「自己完結型の宗教的星座」と見なされるかもしれないが[ 116] 、各伝統の「理論家と文学者」[116]の間には、 「より広いアイデンティティの感覚、共有された文脈における一貫性の感覚、そして共通の枠組みと地平線への包含の感覚」。[116]

古典的なヒンドゥー教

バラモンは、ヴェーダ後のヒンドゥー教の統合の発展、ヴェーダ文化を地域社会に広め、地域の宗教を地域を超えたバラモン文化に統合する上で重要な役割を果たしました。グプタ朝後のヴェーダーンタ派は、正統なバラモン教文化とヒンドゥー教文化が保存されていたインド南部で発展し、 [123]古代ヴェーダの伝統に基づいて、「ヒンドゥー教の複数の要求に対応」しました。[124]

中世の発展

インドのいくつかの宗教と伝統に共通する分母の概念は、西暦12世紀からさらに発展しました。[125]ローレンゼンは、「家族的類似」の出現と、彼が「中世および現代のヒンドゥー教の始まり」と呼んでいるものが形作られていることをたどる。西暦300〜600年、初期のプラーナの発展と、初期のヴェーダの宗教との連続性。[126]ローレンゼンは、ヒンズー教徒の自己同一性の確立は「対照的なイスラム教徒の他者との相互自己定義のプロセスを通じて」行われたと述べている。[127]ローレンゼンによれば、この「他者の存在」[127]は、さまざまな伝統や学校の間の「ゆるい家族的類似」を認識するために必要である。

インド言語学者のアレクシス・サンダーソンによれば、イスラム教がインドに到着する前は、「サンスクリット語の情報源は、ヴァイディカ、ヴァイアヴァ、シャイヴァ、シャクタ、サウラ、仏教、ジャイナの伝統を区別していましたが、これらの最初の5つを集合体として示す名前はありませんでした。仏教とジャイナ教に反対する」。サンダーソンは、この正式な名前の欠如は、対応するヒンドゥー教の概念が存在しなかったことを意味するものではありません。西暦1千年紀の終わりまでに、仏教やジャイナ教とは異なる信念と伝統の概念が出現しました。[web 5]この複雑な伝統は、特定の反律法主義のタントラ運動を除いて、現在ヒンドゥー教であるもののほとんどすべてをそのアイデンティティで受け入れました。[ウェブ5]当時の保守的な思想家の中には、特定のシャクティ派、ヴィシュヌ派、シャクティ派のテキストや慣習がヴェーダと一致しているか、全体として無効であるかを疑問視する人もいました。穏健派、そしてその後のほとんどの正統派学者は、いくつかのバリエーションはあるものの、彼らの信念の基礎、儀式の文法、精神的な前提、そして救済論は同じであることに同意しました。「このより大きな一体感」は、「ヒンドゥー教と呼ばれるようになった」とサンダーソンは述べています。[ウェブ5]

ニコルソンによれば、すでに12世紀から16世紀の間に、「特定の思想家は、ウパニシャッド、叙事詩、プラーナ、および遡及的に主流の「6つのシステム」( saddarsana)として知られている学校の多様な哲学的教えを単一の全体として扱い始めました。ヒンドゥー哲学。」[129]「哲学的区別の曖昧さ」の傾向もバーリーによって指摘されている。[130]ハッカーはこれを「宗教的包括主義」と呼び[117]、マイケルズは「特定の習慣」について語っています。[15]ローレンゼンは、イスラム教徒とヒンズー教徒の間の相互作用[131]と、「[132] [51] 1800年よりかなり前に始まった。[133]マイケルズは次のように述べている。

植民地時代と新ヴェーダーンタ

この宗教的包括主義[135]は、19世紀と20世紀にヒンドゥー教改革運動と新ヴェーダーンタ[136]によってさらに発展し、現代のヒンドゥー教の特徴となっています。[117]

「単一世界の宗教的伝統」としての「ヒンドゥー教」に関する概念と報告[137]は、19世紀の改宗宣教師とヨーロッパのインド学者によっても普及しました。インドの宗教に関する彼らの情報と、宣教師オリエンタリストがヒンドゥー教であると推定したアニミストの観察に対して。[137] [79] [138]これらの報告は、ヒンドゥー教についての認識に影響を与えた。ペニントンなどの学者は、植民地時代の論争の報告が、ヒンドゥー教が悪魔への奉仕に捧げられた単なる神秘的な異教であるという偽造されたステレオタイプにつながったと述べていますが[注20]、他の学者は植民地時代の構造がヴェーダ、バガヴァッドギーター、マヌ法典などのテキストは、ヒンドゥー教の本質であり、「ヒンドゥー教の教義」とヴェーダーンタ派(特にアドヴァイタヴェーダーンタ派)との現代的な関連において、ヒンドゥー教の神秘的な性質の典型的な例でした。[注21]ペニントンは、世界の宗教としてのヒンドゥー教の研究が植民地時代に始まったことに同意する一方で、ヒンドゥー教が植民地時代のヨーロッパ時代の発明であることに同意しません。ヒンズー教徒であると自認する人々の内、古代にさかのぼることができます。[141] [注22]

現代インドと世界

ヒンドゥトヴァ運動は、ヒンドゥー教の統一を広く主張し、その違いを否定し、古代からインドをヒンドゥー教国と見なしてきました。[148]そして、 「ネオ・ヒンドゥトヴァ」としても知られる、インドにおけるヒンドゥー・ナショナリズムの政治的支配の仮定があります。[149] [150]ネパールでは、インドと同様に、ヒンドゥトヴァの優勢も増加している。[151]ヒンドゥー教の範囲は、ヨガやハレクリシュナ運動などの文化的影響により、世界の他の地域でも拡大しています。多くの宣教師組織、特にイスコンによるものであり、これはインドのヒンズー教徒が世界の他の国々に移住したことによるものでもあります。[152] [153]ヒンドゥー教は、多くの西側諸国と一部のアフリカ諸国で急速に成長しています。【注23】

信念

ヒンドゥー教の信仰における著名なテーマには、ダルマ(倫理/義務)、輪廻(情熱とその結果としての誕生、生、死、再生の継続的なサイクル)、カルマ(行動、意図、結果)が含まれます(ただし、これらに限定されません)。 )、モクシャ(愛着と輪廻からの解放)、そしてさまざまなヨガ(道または実践)。[19]

プルシャールタ

プルシャールタは人間の生活の目的を指します。古典的なヒンドゥー思想は、プルシャールタとして知られる人間の生活の4つの適切な目標または目的を受け入れます。[16] [17]

だるま(義、倫理)

ダルマは、ヒンドゥー教における人間の第一の目標と考えられています。[156]ダルマの概念には、生命と宇宙を可能にする秩序であるrta [157]に一致すると見なされる行動が含まれ、義務、権利、法律、行動、美徳、および「正しい生き方」が含まれます。[158]ヒンドゥー教のダルマには、各個人の宗教的義務、道徳的権利および義務、ならびに社会秩序、正しい行動、および善良な行動を可能にする行動が含まれます。[158]ダルマ、ヴァン・ブイテネンによれば、[159]それは、すべての既存の存在が世界の調和と秩序を維持するために受け入れ、尊重しなければならないものです。それは、ヴァン・ブイテネンが、自分の本性と真の召しの追求と実行であり、したがって宇宙コンサートで自分の役割を果たしていると述べています。[159] Brihadaranyaka Upanishadは、次のように述べています。

マハーバーラタでは、クリシュナはダルマをこの世の事柄と他の世俗的な事柄の両方を支持するものと定義しています。(Mbh 12.110.11)。サナータニーという言葉は、永遠、多年生、または永遠を意味します。したがって、サナータニーダルマは、始まりも終わりもないダルマであることを意味します。[162]

Artha(生計、富)

Arthaは、生計、義務、および経済的繁栄のための富の客観的かつ好意的な追求です。それには、政治的生活、外交、物質的な幸福が含まれます。アーサの概念には、すべての「生きがい」、自分がなりたい状態になることを可能にする活動とリソース、富、キャリア、経済的安全が含まれます。[163]アルタの適切な追求は、ヒンドゥー教における人間の生活の重要な目的と考えられています。[164] [165]

カーマ(官能的な喜び)

カーマ(サンスクリット語、パリ語:काम)は、性的な意味の有無にかかわらず、欲望、願い、情熱、憧れ、感覚の喜び、人生の美的楽しみ、愛情、または愛を意味します。[166] [167]ヒンドゥー教では、カーマは、ダルマ、アルタ、モクシャを犠牲にすることなく追求された場合、人間の生活の本質的で健康的な目標と見なされています。[168]

Mokṣa(解放、saṃsāraからの解放)

モクシャ(サンスクリット語:मोक्ष、ローマ字: mokṣa)またはムクティ(サンスクリット語:मुक्ति)は、ヒンドゥー教の究極の最も重要な目標です。ある意味で、モクシャは悲しみ、苦しみ、輪廻(誕生-再生サイクル)からの解放に関連する概念です。人生の後、特にヒンドゥー教の有神論の学校でのこの終末論的サイクルからの解放は、モクシャと呼ばれています。[159] [169] [170]アートマンcqプルシャの破壊不可能性を信じているため、 [ 171]死は宇宙の自己に関して重要でないと見なされています。[172]

モクシャの意味は、ヒンドゥー教のさまざまな流派の間で異なります。たとえば、Advaita Vedantaは、モクシャに到達した後、人は自分の本質、自己を純粋な意識または証人意識として知っており、それをブラフマンと同一であると識別していると考えています。[173] [174]モクシャ州のドヴァイタ(二元論)学校の信者は、個々のエッセンスをブラフマンとは異なるが非常に近いものとして識別し、モクシャに到達した後、ロカ(天国)で永遠を過ごすことを期待しています。ヒンドゥー教の有神論の学校にとって、モクシャは輪廻からの解放ですが、一元論の学校などの他の学校にとって、モクシャは現在の生活で可能であり、心理的な概念です。[175] [173][176] [177] [174]ドイツ語によると、モクシャは後者に対する超越的な意識であり、自己実現、自由、そして「宇宙全体を自己として実現する」という完璧な状態です。[175] [173] [177] これらのヒンドゥー教の学校のモクシャは、クラウス・クロスターマイアーを示唆している[174]。これまで束縛されていた能力のない環境、制限のない生活への障害を取り除き、人が完全な意味でより真に人になることを可能にすることを意味します。この概念は、ブロックされてシャットアウトされた、創造性、思いやり、理解という未使用の人間の可能性を前提としています。モクシャは、苦しみの生命再生サイクルからの解放以上のものです(saṃsāra)。ヴェーダーンタ派はこれを2つに分けています:Jivanmukti(この人生の解放)とVidehamukti(死後の解放)。[174] [178] [179]

カルマと輪廻

カルマは文字通り行動、仕事、または行為として解釈され[180]、「因果関係の道徳法」のヴェーダ理論も指します。[181] [182]理論は、(1)倫理的または非倫理的である可能性のある因果関係の組み合わせです。(2)倫理化、つまり良い行動または悪い行動は結果をもたらします。(3)再生。[183]カルマ理論は、過去の彼または彼女の行動を参照して、個人の現在の状況を説明するものとして解釈されます。これらの行動とその結果は、人の現在の生活、またはヒンドゥー教のいくつかの学校によると、過去の生活にある可能性があります。[183] [184]この誕生、生、死、そして再生のサイクルは、輪廻と呼ばれます。輪廻からモクシャまでの解放は、永続的な幸福と平和を保証すると信じられています。[185] [186]ヒンズー教の経典は、未来は自由意志から導き出された現在の人間の努力と状況を設定する過去の人間の行動の両方の関数であると教えています。[187]

神の概念

ヒンドゥー教は、さまざまな信念を持つ多様な思考システムです。[61] [188] [web 12]神の概念は複雑であり、各個人とそれに続く伝統と哲学に依存します。それは、単一神教と呼ばれることもあります(つまり、他の人の存在を受け入れながら単一の神に献身することを含みます)が、そのような用語は一般化されすぎています。[189] [190]

リグ・ヴェーダのナサディヤ・スクタ(クリエーション・ヒム)は、宇宙を創造したもの、神とザ・ワンの概念、さらには宇宙がどのようにして生まれたのかを知っています。[195] [196]リグ・ヴェーダは、単一神教的な方法で、優れたものでも劣ったものでもない、さまざまな神々を称賛しています。[197]賛美歌は繰り返し一つの真実と一つの究極の現実を指します。ヴェーダ文学の「一つの真実」、現代の学問では、一神教、一元論、そして自然の偉大な出来事とプロセスの背後にある神聖な隠された原則として解釈されてきました。[198]

ヒンズー教徒は、すべての生き物には自己があると信じています。すべての人のこの真の「自己」は、アートマンと呼ばれます。自己は永遠であると信じられています。[199]ヒンドゥー教の一元論的/汎神論的(非二元論的)神学(Advaita Vedanta学校など)によると、このアートマンはブラフマン、最高の精神、または究極の現実とは区別されません。[200]不二一元論によると、人生の目標は、自分の自己が至高の自己と同一であることを認識することです。、最高の自己がすべての人に存在し、すべての人生が相互に関連していて、すべての人生に一体性があること。[201] [202] [203] 二元論的学校(ドヴァイタとバクティ)は、ブラフマンを個々の自己から分離された至高の存在として理解しています。[204]彼らは、宗派に応じて、ヴィシュヌ、ブラフマー、シヴァ、またはシャクティとしてさまざまに至高の存在を崇拝します。神はイシュヴァラ、バガヴァン、パラメシュワラ、デーヴァまたはデヴィと呼ばれています、およびこれらの用語は、ヒンドゥー教のさまざまな学校でさまざまな意味を持っています。[205] [206] [207]

ヒンドゥー教のテキストは多神教の枠組みを受け入れますが、これは一般に、無生物の天然物質に活力とアニメーションを与える神の本質または光度として概念化されています。[208]人間、動物、樹木、川など、あらゆるものに神があります。それは、川、木、自分の仕事の道具、動物や鳥、昇る太陽、友人やゲスト、教師や両親への供物で観察できます。[208] [209] [210]それらがそれ自体で神聖であるのではなく、それぞれを神聖で尊敬に値するものにするのは、これらの神聖なものです。ブッティマーとウォリンが見ているように、この神性の認識はすべてのものに現れており、ヒンドゥー教のヴェーダの基盤をアニミズムとはまったく異なるものにしています。、すべてのものはそれ自体が神聖です。[208]アニミズムの前提は多様性、したがって人間と人間、人間と動物、人間と自然などに関して権力を争う能力の平等を見ている。ヴェーダの見解はこの競争、人間の平等を認識していない自然、または多様性は、すべての人とすべてを統合する圧倒的で相互に関連する単一の神性です。[208] [211] [212]

ヒンドゥー教の経典は、デーヴァ(または女性の形でデーヴァ)と呼ばれる天体を指名します。これは、神または天の存在として英語に翻訳される場合があります。[注24]デーヴァはヒンドゥー教の文化の不可欠な部分であり、芸術、建築、アイコンを通して描かれ、それらについての物語は経典、特にインドの叙事詩とプラーナに関連しています。しかし、彼らはしばしば人格神であるイシュバラとは区別され、多くのヒンズー教徒がイシュバラを崇拝しています。彼らのiṣṭadevatā、または選ばれた理想としてのその特定の症状の1つで。[213] [214]選択は、個人の好み[215]と、地域および家族の伝統の問題です。[215] [注25]多数のデーヴァはバラモンの現れと見なされます。[217]

アバターという言葉はヴェーダの文献には登場しませんが[218] 、ヴェーダ後の文学では動詞の形で登場し、特に西暦6世紀以降のプラーナの文学では名詞として登場します。[219]理論的には、生まれ変わりのアイデアは、他の神々にも適用されていますが、ほとんどの場合、ヒンドゥー教の神ヴィシュヌのアバターに関連付けられています。[220]ヴィシュヌのアバターのさまざまなリストは、ガルーダプラーナの10のダシャーヴァターラとバーガヴァタプラーナの22のアバターを含むヒンドゥー教の経典に登場します。後者は、ヴィシュヌの化身は無数であると付け加えていますが。[221]ヴィシュヌ派のアバターは、ヴィシュヌ派の神学において重要です。女神に基づくシャクティ派の伝統では、デーヴィーのアバターが見つかり、すべての女神は同じ形而上学的なブラフマン[222]とシャクティ (エネルギー)の異なる側面であると見なされます。[223] [224]ガネーシャやシヴァなどの他の神々のアバターも中世のヒンドゥー教のテキストで言及されていますが、これはマイナーで時折あります。[225]

認識論的および形而上学的な理由から、有神論的アイデアと無神論的アイデアの両方が、ヒンドゥー教のさまざまな学校で豊富にあります。たとえば、初期のニヤーヤ学派のヒンドゥー教は非有神論者/無神論者でしたが[226]、後のニヤーヤ学派の学者は神が存在すると主張し、その論理理論を使用して証明を提供しました。[227] [228]他の学校はNyayaの学者に同意しなかった。Samkhya、[229] Mimamsa [230]、およびヒンドゥー教のCarvaka学校は、「神は不必要な形而上学的な仮定であった」と主張して、非有神論者/無神論者でした。[ウェブ13] [231] [232]そのヴァイシェーシカ学校は、自然主義に依存し、すべての問題が永遠であるという別の非有神論的伝統として始まりましたが、後に非創造神の概念を導入しました。[233] [234] [235]ヒンドゥー教のヨガスクールは「人格神」の概念を受け入れ、それをヒンドゥー教に任せて彼または彼女の神を定義した。[236]不二一元論は、神や神の余地がなく、モハンティが「宗教的ではなく精神的」と呼んでいる一元論的で抽象的な自己と一体性をすべてに教えた。[237]ヴェーダーンタのバクティサブスクールは、それぞれの人間とは異なる創造主である神を教えました。[204]

ヒンドゥー教の神はしばしば表され、女性的側面と男性的側面の両方を持っています。神における女性の概念ははるかに顕著であり、シヴァとパールヴァティー(アルダナーリーシュヴァラ)、ヴィシュヌとラクシュミ、ラーダーとクリシュナ、シーターとラーマの組み合わせで明らかです。[238]

グラハム・シュヴァイクによれば、ヒンドゥー教は古代から現在に至るまで、世界の宗教において神聖な女性の存在感が最も強いとされています。[239]女神は、最も難解なサイバの伝統の中心と見なされています。[240]

権限

権威と永遠の真理は、ヒンドゥー教において重要な役割を果たしています。[241]宗教的な伝統と真実は、その神聖なテキストに含まれていると信じられており、それらは賢人、教祖、聖人、またはアバターによってアクセスされ、教えられています。[241]しかし、ヒンドゥー教では、権威の問いかけ、内部の議論、宗教的テキストへの挑戦という強い伝統もあります。ヒンズー教徒は、これが永遠の真理の理解を深め、伝統をさらに発展させると信じています。権威は「[...]共同でアイデアを発展させる傾向のある知的文化を通じて、そして自然の理性の共有された論理に従って仲介された」。[241]ウパニシャッドの物語は、権威者に質問する登場人物を表しています。[241]ケーナ・ウパニシャッドは繰り返しケナに尋ねます。[241]カタ・ウパニシャッドとバガヴァッド・ギーターは、生徒が教師の劣った答えを批判する物語を提示します。[241]シヴァプラーナでは、シヴァはヴィシュヌとブラフマーに質問します。[241]疑いはマハーバーラタで繰り返される役割を果たします。[241]ジャヤデーヴァのギータ・ゴーヴィンダは、ラーダーの性格を介して批判を示しています。[241]

主な伝統

宗派

ヒンドゥー教には中心的な教義上の権威がなく、多くの実践的なヒンドゥー教徒は特定の宗派や伝統に属しているとは主張していません。[242]しかしながら、4つの主要な宗派が学術研究で使用されています:シヴァ派、シャクティ派、スマールタ派、そしてヴィシュヌ派。[33] [34] [35] [36]ヴィシュヌ派の信者は、ヒンズー教徒の大多数です。2番目の大きなコミュニティはシヴァ派です。[243] [244] [245] [246] [注26]これらの宗派は、主に崇拝されている中央の神、伝統、および救済論の見通しが異なります。[248]ヒンドゥー教の宗派は、世界の主要な宗教で見られるものとは異なります。なぜなら、ヒンドゥー教の宗派は、複数の個人を実践している個人とあいまいであり、彼は「ヒンドゥー教の多中心主義」という用語を示唆しているからです。[249]

ヴィシュヌ派は、ヴィシュヌ[注27]と彼のアバター、特にクリシュナとラーマを崇拝する献身的な宗教的伝統です。[251]この宗派の信奉者は、一般的に非禁欲的で、僧侶であり、「親密な愛情、喜び、遊び心のある」クリシュナや他のヴィシュヌのアバターに触発されたコミュニティイベントや献身主義の実践に向けられています。[248]これらの慣習には、コミュニティダンス、キルタンとバジャンの歌、瞑想的で精神的な力があると信じられている音と音楽が含まれることがあります。[252]神殿の崇拝と祭りは、通常、ヴィシュヌ派で精巧に行われています。[253]バガヴァッド・ギーターとラーマーヤナは、ヴィシュヌ志向のプラーナとともに、その有神論的基盤を提供します。[254]哲学的には、彼らの信念はヴェーダーンタ派ヒンドゥー教の二元論のサブスクールに根ざしています。[255] [256]

シヴァ派はシヴァに焦点を当てた伝統です。シヴァ派は禁欲的な個人主義にもっと惹かれ、いくつかのサブスクールがあります。[248]彼らの実践にはバクティスタイルの献身主義が含まれているが、彼らの信念は、アドヴァイタやラージャヨガなどの非二元的で一元論的なヒンドゥー教の学校に傾いている。[257] [252]一部のシヴァ派は寺院で崇拝しているが、他のシヴァ派はヨガを強調し、シヴァと一体になるよう努めている。[258]アバターは珍しく、一部のシヴァ派は神を男性と女性の原則の融合として、半分は男性、半分は女性として視覚化します(Ardhanarishvara)。シヴァ派はシャクティ派と関係があり、シャクティはシヴァの配偶者と見なされています。[257]コミュニティのお祝いには、フェスティバルや、クンブメーラなどの巡礼へのヴィシュヌ派の参加が含まれます。[259]シヴァ派は、カシミールからネパールにかけてのヒマラヤ北部、および南インドでより一般的に行われている。[260]

シャクティ派は、宇宙の母としてのシャクティまたはデヴィの女神崇拝に焦点を当てており[248] 、アッサムやベンガルなどのインドの北東部および東部の州で特に一般的です。デビは、シヴァの配偶者であるパールヴァティーのような穏やかな形で描かれています。または、カーリーやドゥルガのような激しい戦士の女神として。シャクティ派の信者は、シャクティ派を男性の原則の根底にある力として認識しています。シャクティ派はタントラの実践にも関連しています。[261]地域の祭典にはお祭りが含まれ、その中には行列や海や他の水域への偶像の浸水が含まれるものもあります。[262]

スマールタ派は、シヴァ、ヴィシュヌ、シャクティ、ガネーシャ、スーリヤ、スカンダなど、すべての主要なヒンドゥー教の神々に同時に崇拝を集中させています。[263]スマールタ派の伝統は、ヒンドゥー教がバラモン教と地元の伝統との相互作用から出現した西暦の初め頃のヒンドゥー教の(初期の)古典派時代に発展した。[264] [265]スマールタ派の伝統は、アドヴァイタヴェーダーンタと一致しており、属性のある神(サグナブラフマン)の崇拝を属性のない神を最終的に実現するための旅と見なした創設者または改革者と見なしています( nirguna Brahman、Atman、Self-knowledge)。[266][267]スマールタ派という用語は、ヒンドゥー教のスムリティのテキストに由来します。これは、テキストの伝統を覚えている人を意味します。[257] [268]このヒンドゥー教の宗派は、哲学的なジュニャーナヨガ、経典の研究、反省、神との自己の一体性の理解を求める瞑想の道を実践しています。[257] [269]

ヒンドゥー教の伝統の人口統計学的歴史や傾向について利用できる国勢調査データはありません。[270]推定値は、ヒンドゥー教のさまざまな伝統における支持者の相対的な数によって異なります。ジョンソンとグリムによる2010年の推定によると、Vaishnavismの伝統は、ヒンズー教徒の約6億4100万または67.6%の最大のグループであり、2億5200万または26.6%のシャクティ派、3000万または3.2%のシャクティ派、およびネオを含む他の伝統が続きます。ヒンドゥー教と改革ヒンドゥー教は2500万または2.6%。[243]対照的に、ジョーンズとライアンによれば、シヴァ派はヒンドゥー教の最大の伝統である。[247]

民族

ヒンドゥー教は伝統的に多民族または多民族の宗教です。インド亜大陸では、多くのインド・アーリア人、ドラヴィダ人、その他の南アジアの民族グループ、たとえばメイテイ族(インド北東部のマニプール州のチベット・ビルマ民族)に広まっています。

さらに、古代と中世では、ヒンドゥー教は、西の アフガニスタン(カブール)から東の東南アジアのほぼすべて(カンボジア、ベトナム、インドネシア)を含む、アジアの多くのインド化された王国、大インドの国家宗教でした。 、部分的にフィリピン)–そして15世紀までに、バリ人[273 ] [ 274 ]やインドネシアのテンゲレス人[275] 、ベトナムのチャム族。[276]また、分割後にインドに移住したアフガニスタンのパシュトゥーン人の小さなコミュニティは、ヒンドゥー教にコミットし続けている。[277]

ガーナには多くの新しい民族のガーナヒンドゥー教徒がいます。彼らはスワミガナナンドサラスワティとアフリカのヒンドゥー教修道院の働きによりヒンドゥー教に改宗しました[278] 20世紀初頭から、ババプレマナンダバラティ(1858–1914)の軍隊によって)、スワミヴィヴェーカーナンダ、ACバクティブダンタスワミプラブパダおよび他の宣教師、ヒンドゥー教は西洋の人々の間で一定の分布を得ました。[279]

経典

ヒンドゥー教の古代の経典はサンスクリット語にあります。これらのテキストは、ShrutiとSmritiの2つに分類されます。Shrutiはapauruṣeyāであり、「人でできていない」が、リシ(予言者)に明らかにされ、最高の権威を持っていると見なされ、スムリティは人造で二次的な権威を持っています。[280]それらはダルマの2つの最高の源であり、他の2つはŚiṣṭaĀchāra/Sadāchara(高貴な人々の行為)そして最後にĀtmatuṣṭi(「自分に喜ばれるもの」)です[注29]

ヒンドゥー教の経典は、何世紀にもわたって、書き留められる前に、世代を超えて作曲され、記憶され、口頭で伝えられました。[281] [282]何世紀にもわたって、賢人は教えを洗練し、シュルティとスムリティを拡大し、ヒンドゥー教の6つの古典的な学校の認識論的および形而上学的理論を備えたシャーストラを開発しました。

シュルティ(聞こえるもの)[283]は主に、ヒンドゥー教の経典の最も初期の記録を形成するヴェーダを指し、古代の賢人(リシ)に明らかにされた永遠の真実と見なされています。[284] 4つのヴェーダがあります–リグヴェーダ、サマヴェーダ、ヤジュルヴェーダ、アタルヴァヴェーダ。各ヴェーダは、サンヒター(マントラと祝祷)、アランヤカ(儀式、儀式、犠牲、象徴的な犠牲に関するテキスト)、ブラーフマナの4つの主要なテキストタイプに細分類されています。(儀式、儀式、犠牲についての解説)、およびウパニシャッド(瞑想、哲学、精神的知識について議論するテキスト)。[285] [286] [287]ヴェーダの最初の2つの部分はその後Karmakāṇḍa(儀式的な部分)と呼ばれ、最後の2つはJñānakāṇḍa(知識の部分、精神的な洞察と哲学的な教えについて議論する)を形成します。[288] [289] [290] [291]

ウパニシャッドはヒンドゥー哲学思想の基盤であり、多様な伝統に大きな影響を与えてきました。[292] [293] [146]シュルティス(ヴェーダコーパス)の中で、それらだけがヒンドゥー教徒の間で広く影響力があり、ヒンドゥー教の卓越した経典と見なされており、彼らの中心的な考えはその思想と伝統に影響を与え続けています。[292] [144] Sarvepalli Radhakrishnanは、ウパニシャッドが登場して以来、支配的な役割を果たしてきたと述べています。[294]ヒンドゥー教には108のムクティカー・ウパニシャッドがあり、そのうち10から13は、学者によってプリンシパル・ウパニシャッドとしてさまざまに数えられています。[291] [295] スムリティ(「記憶」)の中で最も注目に値するのは、ヒンドゥー教の叙事詩とプラーナです。叙事詩はマハーバーラタとラーマーヤナで構成されています。バガヴァッド・ギーターはマハーバーラタの不可欠な部分であり、ヒンドゥー教の最も人気のある聖典の1つです。[296]それは時々ギトパニシャッドと呼ばれ、その後シュルティ(「聞いた」)カテゴリーに入れられ、内容はウパニシャッドである。[297] cから構成され始めたプラーナ。300 CE以降、[298]には広範な神話が含まれており、鮮やかな物語を通してヒンドゥー教の一般的なテーマを配布する上で中心的な役割を果たしています。Theヨガスートラは、20世紀に再び人気を博したヒンドゥーヨガの伝統の古典的なテキストです。[299] 19世紀以来、インドのモダニストはヒンドゥー教の「アーリア人の起源」を再主張し、タントラの要素からヒンドゥー教を「浄化」し[92]、ヴェーダの要素を高めてきた。ヴィヴェーダのようなヒンドゥー教のモダニストは、ヴェーダを精神世界の法則と見なしています。[300] [301]タントラの伝統では、アガマは権威ある経典またはシヴァからシャクティへの教えを指し、 [ 302]ニガマスはヴェーダとシャクティからシヴァへの教えを指します。[302]ヒンドゥー教のアガミック学校では、ヴェーダ文学とアガマは等しく権威があります。[303] [304]

練習

儀式

ほとんどのヒンズー教徒は自宅で宗教的な儀式を守っています。[306]儀式は、地域、村、個人によって大きく異なります。ヒンドゥー教では必須ではありません。儀式の性質と場所は個人の選択です。一部の敬虔なヒンズー教徒は、入浴後の夜明けの礼拝(通常は家族の神社で、通常はランプを点灯し、神の像の前に食材を提供することを含みます)、宗教的な台本からの朗読、バジャン(祈りの賛美歌)の歌、ヨガなどの毎日の儀式を行います瞑想、マントラの唱えなど。[307]

火のオブレーション(ヤグナ)のヴェーダの儀式とヴェーダの賛美歌の詠唱は、ヒンドゥー教の結婚式などの特別な機会に観察されます。[308]死後の儀式など、他の主要なライフステージのイベントには、ヤグナやヴェーダのマントラの詠唱が含まれます。[ウェブ15]

The words of the mantras are "themselves sacred,"[309] and "do not constitute linguistic utterances."[310] Instead, as Klostermaier notes, in their application in Vedic rituals they become magical sounds, "means to an end."[note 30] In the Brahmanical perspective, the sounds have their own meaning, mantras are considered "primordial rhythms of creation", preceding the forms to which they refer.[310] By reciting them the cosmos is regenerated, "by enlivening and nourishing the forms of creation at their base. As long as the purity of the sounds is preserved, the recitation of the mantras will be efficacious, irrespective of whether their discursive meaning is understood by human beings."[310][230]

Life-cycle rites of passage

Major life stage milestones are celebrated as sanskara (saṃskāra, rites of passage) in Hinduism.[311][312] The rites of passage are not mandatory, and vary in details by gender, community and regionally.[313] Gautama Dharmasutras composed in about the middle of 1st millennium BCE lists 48 sanskaras,[314] while Gryhasutra and other texts composed centuries later list between 12 and 16 sanskaras.[311][315] The list of sanskaras in Hinduism include both external rituals such as those marking a baby's birth and a baby's name giving ceremony, as well as inner rites of resolutions and ethics such as compassion towards all living beings and positive attitude.[314] The major traditional rites of passage in Hinduism include[313] Garbhadhana (pregnancy), Pumsavana (rite before the fetus begins moving and kicking in womb), Simantonnayana (parting of pregnant woman's hair, baby shower), Jatakarman (rite celebrating the new born baby), Namakarana (naming the child), Nishkramana (baby's first outing from home into the world), Annaprashana (baby's first feeding of solid food), Chudakarana (baby's first haircut, tonsure), Karnavedha (ear piercing), Vidyarambha (baby's start with knowledge), Upanayana (entry into a school rite),[316][317] Keshanta and Ritusuddhi (first shave for boys, menarche for girls), Samavartana (graduation ceremony), Vivaha (wedding), Vratas (fasting, spiritual studies) and Antyeshti (cremation for an adult, burial for a child).[318] In contemporary times, there is regional variation among Hindus as to which of these sanskaras are observed; in some cases, additional regional rites of passage such as Śrāddha (ritual of feeding people after cremation) are practiced.[313][319]

Bhakti (worship)

Bhakti refers to devotion, participation in and the love of a personal god or a representational god by a devotee.[web 16][320] Bhakti-marga is considered in Hinduism to be one of many possible paths of spirituality and alternative means to moksha.[321] The other paths, left to the choice of a Hindu, are Jnana-marga (path of knowledge), Karma-marga (path of works), Rāja-marga (path of contemplation and meditation).[322][323]

Bhakti is practiced in a number of ways, ranging from reciting mantras, japas (incantations), to individual private prayers in one's home shrine,[324] or in a temple before a murti or sacred image of a deity.[325][326] Hindu temples and domestic altars, are important elements of worship in contemporary theistic Hinduism.[327] While many visit a temple on special occasions, most offer daily prayers at a domestic altar, typically a dedicated part of the home that includes sacred images of deities or gurus.[327]

One form of daily worship is aarti, or “supplication,” a ritual in which a flame is offered and “accompanied by a song of praise.”[328] Notable aartis include Om Jai Jagdish Hare, a prayer to Vishnu, Sukhakarta Dukhaharta, a prayer to Ganesha.[329][330] Aarti can be used to make offerings to entities ranging from deities to “human exemplar[s].”[328] For instance, Aarti is offered to Hanuman, a devotee of God, in many temples, including Balaji temples, where the primary deity is an incarnation of Vishnu.[331] In Swaminarayan temples and home shrines, aarti is offered to Swaminarayan, considered by followers to be supreme God.[332]

Other personal and community practices include puja as well as aarti,[333] kirtan, or bhajan, where devotional verses and hymns are read or poems are sung by a group of devotees.[web 17][334] While the choice of the deity is at the discretion of the Hindu, the most observed traditions of Hindu devotion include Vaishnavism, Shaivism, and Shaktism.[335] A Hindu may worship multiple deities, all as henotheistic manifestations of the same ultimate reality, cosmic spirit and absolute spiritual concept called Brahman.[336][337][217] Bhakti-marga, states Pechelis, is more than ritual devotionalism, it includes practices and spiritual activities aimed at refining one's state of mind, knowing god, participating in god, and internalizing god.[338][339] While bhakti practices are popular and easily observable aspect of Hinduism, not all Hindus practice bhakti, or believe in god-with-attributes (saguna Brahman).[340][341] Concurrent Hindu practices include a belief in god-without-attributes, and god within oneself.[342][343]

Festivals

Hindu festivals (Sanskrit: Utsava; literally: "to lift higher") are ceremonies that weave individual and social life to dharma.[344][345] Hinduism has many festivals throughout the year, where the dates are set by the lunisolar Hindu calendar, many coinciding with either the full moon (Holi) or the new moon (Diwali), often with seasonal changes.[346] Some festivals are found only regionally and they celebrate local traditions, while a few such as Holi and Diwali are pan-Hindu.[346][347] The festivals typically celebrate events from Hinduism, connoting spiritual themes and celebrating aspects of human relationships such as the Sister-Brother bond over the Raksha Bandhan (or Bhai Dooj) festival.[345][348] The same festival sometimes marks different stories depending on the Hindu denomination, and the celebrations incorporate regional themes, traditional agriculture, local arts, family get togethers, Puja rituals and feasts.[344][349]

Some major regional or pan-Hindu festivals include:

Pilgrimage

Many adherents undertake pilgrimages, which have historically been an important part of Hinduism and remain so today.[350] Pilgrimage sites are called Tirtha, Kshetra, Gopitha or Mahalaya.[351][352] The process or journey associated with Tirtha is called Tirtha-yatra.[353] According to the Hindu text Skanda Purana, Tirtha are of three kinds: Jangam Tirtha is to a place movable of a sadhu, a rishi, a guru; Sthawar Tirtha is to a place immovable, like Benaras, Haridwar, Mount Kailash, holy rivers; while Manas Tirtha is to a place of mind of truth, charity, patience, compassion, soft speech, Self.[354][355] Tīrtha-yatra is, states Knut A. Jacobsen, anything that has a salvific value to a Hindu, and includes pilgrimage sites such as mountains or forests or seashore or rivers or ponds, as well as virtues, actions, studies or state of mind.[356][357]

Pilgrimage sites of Hinduism are mentioned in the epic Mahabharata and the Puranas.[358][359] Most Puranas include large sections on Tirtha Mahatmya along with tourist guides,[360] which describe sacred sites and places to visit.[361][362][363] In these texts, Varanasi (Benares, Kashi), Rameshwaram, Kanchipuram, Dwarka, Puri, Haridwar, Sri Rangam, Vrindavan, Ayodhya, Tirupati, Mayapur, Nathdwara, twelve Jyotirlinga and Shakti Peetha have been mentioned as particularly holy sites, along with geographies where major rivers meet (sangam) or join the sea.[364][359] Kumbhamela is another major pilgrimage on the eve of the solar festival Makar Sankranti. This pilgrimage rotates at a gap of three years among four sites: Prayag Raj at the confluence of the Ganges and Yamuna rivers, Haridwar near source of the Ganges, Ujjain on the Shipra river and Nasik on the bank of the Godavari river.[365] This is one of world's largest mass pilgrimage, with an estimated 40 to 100 million people attending the event.[365][366][web 18] At this event, they say a prayer to the sun and bathe in the river,[365] a tradition attributed to Adi Shankara.[367]

Some pilgrimages are part of a Vrata (vow), which a Hindu may make for a number of reasons.[368][369] It may mark a special occasion, such as the birth of a baby, or as part of a rite of passage such as a baby's first haircut, or after healing from a sickness.[370][371] It may, states Eck, also be the result of prayers answered.[370] An alternative reason for Tirtha, for some Hindus, is to respect wishes or in memory of a beloved person after his or her death.[370] This may include dispersing their cremation ashes in a Tirtha region in a stream, river or sea to honor the wishes of the dead. The journey to a Tirtha, assert some Hindu texts, helps one overcome the sorrow of the loss.[370][note 31]

Other reasons for a Tirtha in Hinduism is to rejuvenate or gain spiritual merit by traveling to famed temples or bathe in rivers such as the Ganges.[374][375][376] Tirtha has been one of the recommended means of addressing remorse and to perform penance, for unintentional errors and intentional sins, in the Hindu tradition.[377][378] The proper procedure for a pilgrimage is widely discussed in Hindu texts.[379] The most accepted view is that the greatest austerity comes from traveling on foot, or part of the journey is on foot, and that the use of a conveyance is only acceptable if the pilgrimage is otherwise impossible.[380]

Culture

「ヒンドゥー教の文化」という用語は、お祭りや服装規定など、宗教に関連する文化の側面を意味し、主にインドや東南アジアの文化から着想を得たヒンドゥー教徒が続きます。ヒンドゥー教にはさまざまな文化が混在しており、主にインド文化圏の一部を中心に、多くの国の文化にも影響を与えてきました。

建築

Hindu architecture is the traditional system of Indian architecture for structures such as temples, monasteries, statues, homes, market places, gardens and town planning as described in Hindu texts.[381][382] The architectural guidelines survive in Sanskrit manuscripts and in some cases also in other regional languages. These texts include the Vastu shastras, Shilpa Shastras, the Brihat Samhita, architectural portions of the Puranas and the Agamas, and regional texts such as the Manasara among others.[383][384]

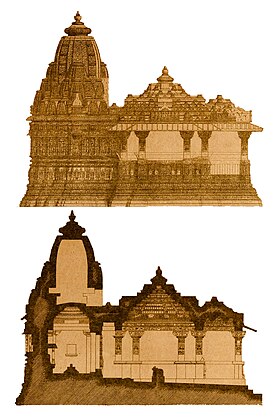

ヒンドゥー建築の最も重要で特徴的で多くの生き残った例は、グプタ朝にまでさかのぼる石、レンガ、岩を切り出した建築の生き残った例を残した建築の伝統を持つヒンドゥー寺院です。これらの建築は、古代ペルシャとヘレニズムの建築の影響を受けていました。[385]宮殿、家、都市など、現代に生き残ったヒンドゥー建築ははるかに少ない。遺跡と考古学の研究は、インドの初期の世俗的な建築の見方を提供します。[386]

インドの宮殿と市民の建築史に関する研究は、比較的豊富なインド北部と西部のムガル帝国とインド・イスラーム建築に主に焦点を当ててきました。インドの他の地域、特に南部では、ヴィジャヤナガル帝国とナヤカ朝の寺院、廃墟となった都市、世俗的な空間など、16世紀を通じてヒンドゥー建築が繁栄し続けました。[387] [388]世俗的な建築はインドの宗教に反対することは決してありませんでした、そしてそれは世俗的なものに触発されて適応されたヒンドゥー教の寺院で見られるような神聖な建築です。さらに、ハールは、世俗的な建築のミニチュア版を見つけることができるのは、寺院の壁、柱、トラナ、マダパムのレリーフにあると述べています。[389]美術

カレンダー

ヒンドゥー暦、パンチャンガ(サンスクリット語:पञ्चाङ्ग、マラティ: पंचांग)またはパンジカは、インドの亜大陸と東南アジアで伝統的に使用されているさまざまな太陰太陽暦の1つです。彼らは、太陽周期の恒星年に基づく計時と3年ごとの月の周期の調整について同様の基本的な概念を採用していますが、月の周期または太陽の周期と月の名前、および新年を考慮する時期との相対的な強調が異なります。始めること。[390]さまざまな地域のカレンダーの中で、最も研究され、知られているヒンドゥー暦は、南インドのデカン地域で見つかったShalivahana Shaka 、インドのネパール、北部、中央地域で見つかったVikram Samvat (Bikrami)です。これらはすべて月の周期を強調しています。彼らの新年は春に始まります。タミル・ナードゥやケララなどの地域では、太陽の周期が強調されており、これはタミル暦(タミル暦はヒンドゥー暦のように月の名前を使用します)およびマラヤラム暦と呼ばれ、これらは西暦1千年紀の後半に起源があります。[390] [391]ヒンドゥー暦はパンチャンガムと呼ばれることもあります(पञ्चाङ्ग)、これは東インドではパンジカとしても知られています。[392]

古代ヒンドゥー暦の概念設計は、ヘブライ暦、中国暦、バビロニア暦にも見られますが、グレゴリアン暦とは異なります。[393] 12の月の周期(354の月の日) [394]とほぼ365の太陽の日の不一致を調整するために月に日を追加するグレゴリオ暦とは異なり、ヒンドゥー暦は月の月の整合性を維持しますが、挿入します祭りや作物関連の儀式が適切な時期に行われるようにするために、複雑な規則により、32〜33か月に1回の追加の1か月。[393] [391]

ヒンドゥー暦はヴェーダ時代からインド亜大陸で使用されており、特にヒンドゥー教の祭りの日付を設定するために、世界中のヒンドゥー教徒によって使用され続けています。インドの初期の仏教徒のコミュニティは、古代のヴェーダ暦、後にヴィクラマ暦、そして地元の仏教暦を採用しました。仏教の祭りは、月のシステムに従ってスケジュールされ続けています。[395]カンボジア、ラオス、ミャンマー、スリランカ、タイの仏暦と伝統的な太陰太陽暦も、古いバージョンのヒンドゥー暦に基づいています。同様に、古代ジャイナ教伝統は、お祭り、テキスト、碑文のヒンドゥー暦と同じ太陰太陽暦に従っています。しかし、仏教とジャイナ教の計時システムは、仏陀とマハーヴィーラの生涯を基準点として使用しようと試みました。[396] [397] [398]

ヒンドゥー暦は、ヒンドゥー占星術や干支システムの実践だけでなく、主の特別な出現日やエカダシなどの断食日を観察するためにも重要です。人と社会

ヴァルナ

Hindu society has been categorised into four classes, called varṇas. They are the Brahmins: Vedic teachers and priests; the Kshatriyas: warriors and kings; the Vaishyas: farmers and merchants; and the Shudras: servants and labourers.[399] The Bhagavad Gītā links the varṇa to an individual's duty (svadharma), inborn nature (svabhāva), and natural tendencies (guṇa).[400] The Manusmriti categorises the different castes.[web 19] Some mobility and flexibility within the varṇas challenge allegations of social discrimination in the caste system, as has been pointed out by several sociologists,[401][402] although some other scholars disagree.[403] Scholars debate whether the so-called caste system is part of Hinduism sanctioned by the scriptures or social custom.[404][web 20][note 32] And various contemporary scholars have argued that the caste system was constructed by the British colonial regime.[405]

A renunciant man of knowledge is usually called Varṇatita or "beyond all varṇas" in Vedantic works. The bhiksu is advised to not bother about the caste of the family from which he begs his food. Scholars like Adi Sankara affirm that not only is Brahman beyond all varṇas, the man who is identified with Him also transcends the distinctions and limitations of caste.[406]

Yoga

In whatever way a Hindu defines the goal of life, there are several methods (yogas) that sages have taught for reaching that goal. Yoga is a Hindu discipline which trains the body, mind, and consciousness for health, tranquility, and spiritual insight.[407] Texts dedicated to yoga include the Yoga Sutras, the Hatha Yoga Pradipika, the Bhagavad Gita and, as their philosophical and historical basis, the Upanishads. Yoga is means, and the four major marga (paths) of Hinduism are: Bhakti Yoga(愛と献身の道)、カルマ・ヨーガ(正しい行動の道)、ラージャ・ヨーガ(瞑想の道)、そしてジュニャーナ・ヨガ(知恵の道)[408]個人は、他のヨガよりも1つまたはいくつかのヨガを好むかもしれません、彼または彼女の傾向と理解によると。あるヨガの練習は他のヨガを排除するものではありません。運動としてのヨガの現代的な実践(伝統的にハタヨガ)は、ヒンドゥー教と争われた関係を持っています。[409]

象徴主義

ヒンドゥー教は、芸術、建築、文学、崇拝の神聖さを表すために、象徴主義と図像学のシステムを開発しました。これらのシンボルは、経典や文化的伝統からその意味を獲得します。音節のオーム(ブラフマンとアートマンを表す)はヒンドゥー教そのものを表すように成長しましたが、スワスティカの記号などの他のマーキングは縁起の良いものを表し[410]、額のティラカ(文字通り、種)は精神的な第三の目の場所と考えられています目、[411]は、儀式または通過の儀式への儀式的な歓迎、祝福、または参加を示します。[412]線のある手の込んだティラカは、特定の宗派の信者を特定することもあります。花、鳥、動物、楽器、対称的な曼荼羅の絵、オブジェクト、偶像はすべて、ヒンドゥー教の象徴的な図像の一部です。[413] [414]

Ahiṃsāと食習慣

ヒンズー教徒は、アヒンサー(非暴力)の実践とすべての生命の尊重を提唱しています。なぜなら、神性は植物や人間以外の動物を含むすべての存在に浸透すると信じられているからです。[415] ahiṃsāという用語はウパニシャッドに登場し[416]、壮大なマハーバーラタ[417]であり、ahiṃsāはパタンジャリのヨガスートラにある5つのヤマ(自制の誓い)の最初のものです。[418]

ahiṃsāに従って、多くのヒンズー教徒はより高い形態の生命を尊重するために菜食主義を受け入れます。肉、魚、卵をまったく食べないインドの厳格な菜食主義者(すべての宗教の信者を含む)の推定値は20%から42%の間で変動しますが、他の菜食主義者はそれほど厳格ではない菜食主義者または非菜食主義者です。[419]肉を食べる人は、肉の生産にジャトカ(クイックデス)法を求め、ハラール(スローブリードデス)法を嫌い、クイックデス法は動物の苦痛を軽減すると信じています。[420] [421]食生活は地域によって異なり、ベンガルのヒンズー教徒とヒンズー教徒はヒマラヤ地域に住んでいます。、または三角州地域で、定期的に肉や魚を食べています。[422]特定の祭りや行事で肉を避ける人もいます。[423]肉を食べる注意深いヒンズー教徒は、ほとんどの場合、牛肉を控えています。ヒンドゥー教は特にBosindicusを神聖であると考えています。[424] [425] [426]ヒンドゥー社会の牛は伝統的に世話人であり母体であると認識されており[427]、ヒンドゥー社会は牛を利己的でない寄付の象徴として尊敬している[428]無私の犠牲、優しさ、寛容。[429]厳格な菜食主義者 を守り続けている多くのヒンズー教徒のグループがあります現代のダイエット。肉、卵、魚介類を含まない食事に固執する人もいます。[430]食べ物は、ヒンドゥー教の信仰において、体、心、精神に影響を及ぼします。[431] [432] ŚāṇḍilyaUpanishad [433]やSvātmārāma [434] [435]などのヒンドゥー教のテキストは、山(高潔な自己拘束)の1つとして三田原(適度に食べる)を推奨しています。バガヴァッド・ギーターは、17.8節から17.10節で、体と心を食物と結びつけています。[436]

シャクティ派の伝統に属するヒンズー教徒[437]や、バリやネパール[438] [439]などの地域のヒンズー教徒は、動物の犠牲を実践しています。[438]犠牲になった動物は、儀式用の食べ物として食べられます。[440]対照的に、Vaishnavaヒンズー教徒は動物の犠牲を嫌い、激しく反対している。[441] [442]ヒンドゥー教では、動物への非暴力の原則が徹底的に採用されているため、動物の犠牲はまれであり[443]、歴史的には痕跡的な限界慣行にまで縮小されています。[444]

機関

寺

ヒンドゥー教の神殿は神の家です。[445]それは、ヒンドゥー教の考えと信念を表現するための象徴性が注入された、人間と神々を結びつけるように設計された空間と構造です。[ 446]寺院には、ヒンドゥー教の宇宙論のすべての要素が組み込まれています。これは、須弥山を表す最も高い尖塔またはドームです。ブラフマーの住居と精神的な宇宙の中心を思い起こさせます。とカルマ。[448] [449]レイアウト、モチーフ、計画、および構築プロセスは、古代の儀式、幾何学的な象徴を暗唱し、ヒンドゥー教のさまざまな学校に固有の信念と価値観を反映しています。[446]ヒンドゥー教の神殿は、多くのヒンドゥー教徒(すべてではない)の精神的な目的地であり、芸術、毎年恒例の祭り、通過儀礼、地域の祭典のランドマークでもあります。[450] [451]

ヒンドゥー教の寺院は、さまざまなスタイル、さまざまな場所にあり、さまざまな建設方法を展開し、さまざまな神や地域の信仰に適応しています。[452]ヒンドゥー教の寺院の2つの主要なスタイルには、南インドで見られるゴープラムスタイルと北インドで見られるナガラスタイルが含まれます。[web 22] [web 23]他のスタイルには、洞窟、森、山の神殿が含まれます。[453]それでも、それらの違いにもかかわらず、ほとんどすべてのヒンドゥー教の寺院は、特定の共通の建築原理、コアアイデア、象徴性およびテーマを共有しています。[446] 多くの寺院には、1つまたは複数の偶像があります(ムルティ)。ブラフマーパダ(寺院の中心)の主な尖塔の下にある偶像とグラブグリヤは、ヒンドゥー寺院の焦点(ダルサナ、光景)として機能します。[454]より大きな神殿では、中央の空間は通常、信者が歩き回り、普遍的な本質であるプルシャ(ブラフマン)を儀式的に周行するための歩行者に囲まれています。[446]

アスラマ

伝統的に、ヒンズー教徒の生活は4つのアーシュラム(段階またはライフステージ。別の意味には修道院が含まれます)に分けられます。[455] 4つのアシュラマは、梵行(学生)、グリハスタ(家主)、ヴァーンプラスタ(引退)、サンニャーサ(放棄)です。[456] 梵行は、学士課程の学生の人生の段階を表しています。グリハスタとは、家族を維持し、家族を育て、子供を教育し、家族中心の厳しい社会生活を送るという義務を伴う、個人の結婚生活を指します。[456]グリハスタの段階はヒンドゥー教の結婚式から始まり、社会学的な文脈ですべての段階の中で最も重要であると考えられてきました。この段階のヒンズー教徒は、善良な生活を追求しただけでなく、他の生活段階の人々を支える食物と富を生み出しました。人類を続けた子孫。[457]ヴァーンプラスタは、人が家計の責任を次の世代に引き継ぎ、助言的な役割を果たし、徐々に世界から撤退する引退段階です。[458] [459]サンニャーサの段階は、放棄と物質的生活からの無関心と分離の状態を示し、一般的に意味のある財産や家(禁欲状態)はなく、モクシャ、平和、そして単純な精神的生活に焦点を当てています。[460] [461] アーシュラマシステムは、ヒンドゥー教のダルマ概念の1つの側面です。[457]人間の生活の4つの適切な目標(プルシャールタ)と組み合わせて、アシュラマシステムは伝統的にヒンズー教徒に充実した生活と精神的な解放を提供することを目的としていました。[457]これらの段階は通常連続的であるが、誰でもサニヤサ(禁欲)段階に入り、梵行段階の後いつでも禁欲になることができる。[462]ヒンドゥー教ではサンニャーサは宗教的に義務付けられておらず、高齢者は家族と自由に暮らすことができる。[463]

出家生活

一部のヒンズー教徒は、解放(モクシャ)または別の形態の精神的完全性を追求して、僧侶生活(サニヤサ)を生きることを選択します。[21]出家生活は、物質的な追求から切り離された、瞑想と精神的な熟考のシンプルで独身的な生活に専念しています。[464]ヒンドゥー教の僧侶は、Sanyāsī、Sādhu、またはSwāmiと呼ばれます。女性の放棄者はSanyāsiniと呼ばれます。ヒンドゥー教の人生の究極の目標であると信じられている彼らの単純なアヒンサー主導のライフスタイルと精神的解放(モクシャ)への献身のために、ヒンドゥー教徒はヒンドゥー社会で高い尊敬を受けています。[461]一部の僧院は僧院に住んでいますが、他の僧院は、彼らの必要に応じて寄付された食べ物や慈善団体に応じて、場所から場所へとさまよっています。[465]

歴史

Hinduism's varied history[19] overlaps or coincides with the development of religion in the Indian subcontinent since the Iron Age, with some of its traditions tracing back to prehistoric religions such as those of the Bronze Age Indus Valley Civilization. It has thus been called the "oldest religion" in the world.[note 33] Scholars regard Hinduism as a synthesis[467][30] of various Indian cultures and traditions,[30][114][467] with diverse roots[28] and no single founder.[468][note 34]

The history of Hinduism is often divided into periods of development. The first period is the pre-Vedic period, which includes the Indus Valley Civilization and local pre-historic religions, ending at about 1750 BCE. This period was followed in northern India by the Vedic period, which saw the introduction of the historical Vedic religion with the Indo-Aryan migrations, starting somewhere between 1900 BCE to 1400 BCE.[473][note 35] The subsequent period, between 800 BCE and 200 BCE, is "a turning point between the Vedic religion and Hindu religions",[476] and a formative period for Hinduism, Jainism and Buddhism. The Epic and Early Puranic period, from c. 200 BCE to 500 CE, saw the classical "Golden Age" of Hinduism (c. 320-650 CE), which coincides with the Gupta Empire. In this period the six branches of Hindu philosophy evolved, namely Samkhya, Yoga, Nyaya, Vaisheshika, Mīmāṃsā, and Vedanta. Monotheistic sects like Shaivism and Vaishnavism developed during this same period through the Bhakti movement. The period from roughly 650 to 1100 CE forms the late Classical period[15] or early Middle Ages, in which classical Puranic Hinduism is established, and Adi Shankara's influential consolidation of Advaita Vedanta.[477]

Hinduism under both Hindu and Islamic rulers from c. 1250–1750 CE,[478][479] saw the increasing prominence of the Bhakti movement, which remains influential today. The colonial period saw the emergence of various Hindu reform movements partly inspired by western movements, such as Unitarianism and Theosophy.[480] In the Kingdom of Nepal, the Unification of Nepal by Rana dynasty was accompanied by the Hinduization of the state and continued till the c. 1950s and after that the Shah dynasty also focused on the basic Hinduization.[481] Indians were hired as plantation labourers in British colonies such as Fiji, Mauritius, Trinidad and Tobago.[citation needed] The Partition of India in 1947 was along religious lines, with the Republic of India emerging with a Hindu majority.[482] During the 20th century, due to the Indian diaspora, Hindu minorities have formed in all continents, with the largest communities in absolute numbers in the United States,[483] and the United Kingdom.[484]

In the 20th–21st century, many missionary organizations such as ISKCON, Sathya Sai Organization, Vedanta Society and so on. have been influential in spreading the core culture of Hinduism outside India.[note 23] There have also been an increase of Hindu identity in politics, mostly in India, Nepal and Bangladesh in the form of Hindutva.[485] The revivalist movement was mainly started and encouraged by many organisations like RSS, BJP and other organisations of Sangh Parivar in India, while there are also many Hindu nationalist parties and organisations such as Shivsena Nepal and RPP in Nepal, HINDRAF in Malaysia, etc.[486][481] In September 2021, the State of New Jersey aligned with the World Hindu Council to declare October as Hindu Heritage Month.

Demographics

Hinduism is a major religion in India. Hinduism was followed by around 79.8% of the country's population of 1.21 billion (2011 census) (966 million adherents).[487] Other significant populations are found in Nepal (23 million), Bangladesh (15 million) and the Indonesian island of Bali (3.9 million).[488] There is also a significant population of Hindus are also present in Pakistan (4 million).[489] The majority of the Vietnamese Cham people also follow Hinduism, with the largest proportion in Ninh Thuận Province.[490] Hinduism is the イスラム教とキリスト教に次ぐ世界で3番目に急成長している宗教であり、2010年から2050年の間に34%の成長率が予測されています。[491]

ヒンズー教徒の割合が最も高い国:

ネパール – 81.3%。[493]

ネパール – 81.3%。[493] インド – 79.8%。[494]

インド – 79.8%。[494] モーリシャス – 48.5%。[495]

モーリシャス – 48.5%。[495] ガイアナ – 28.4%。[496]

ガイアナ – 28.4%。[496] フィジー – 27.9%。[497]

フィジー – 27.9%。[497] ブータン – 22.6%。[498]

ブータン – 22.6%。[498] スリナム – 22.3%。[499]

スリナム – 22.3%。[499] トリニダード・トバゴ – 18.2%。[500]

トリニダード・トバゴ – 18.2%。[500] カタール – 13.8%。[501]

カタール – 13.8%。[501] スリランカ – 12.6%。[502]

スリランカ – 12.6%。[502] バーレーン – 9.8%。[503]

バーレーン – 9.8%。[503] バングラデシュ – 8.5%。[504]

バングラデシュ – 8.5%。[504] レユニオン – 6.8%。【注36】

レユニオン – 6.8%。【注36】 アラブ首長国連邦 – 6.6%。[505]

アラブ首長国連邦 – 6.6%。[505] マレーシア – 6.3%。[506]

マレーシア – 6.3%。[506] クウェート – 6%。[507]

クウェート – 6%。[507] オマーン – 5.5%。[508]

オマーン – 5.5%。[508] シンガポール – 5%。[509]

シンガポール – 5%。[509] インドネシア – 3.86%。[510]

インドネシア – 3.86%。[510] ニュージーランド – 2.62%。[511]

ニュージーランド – 2.62%。[511] セイシェル – 2.4%。[512]

セイシェル – 2.4%。[512] パキスタン – 2.14%。[513]

パキスタン – 2.14%。[513]

人口統計学的に、ヒンドゥー教はキリスト教とイスラム教に次ぐ世界で3番目に大きな宗教です。[514] [515]

| 伝統 | フォロワー | ヒンズー教徒の人口の% | 世界人口の% | フォロワーダイナミクス | ワールドダイナミクス |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ヴィシュヌ派 | 640,806,845 | 67.6 | 9.3 | ||

| シヴァ派 | 252,200,000 | 26.6 | 3.7 | ||

| シャクティ派 | 30,000,000 | 3.2 | 0.4 | ||

| 新ヒンドゥー教 | 20,300,000 | 2.1 | 0.3 | ||

| ヒンドゥー教の改革 | 5,200,000 | 0.5 | 0.1 | ||

| 累積的な | 948,575,000 | 100 | 13.8 |

批判、迫害、そして討論

批判

ヒンドゥー教は、バラモン教とヴァルナシステムの上流階級のバラモンの弁護士を何度も批判してきました。これには、ダリット(またはシュードラ)が社会で最も低いラングと見なされていたため、差別が伴います。[517]これはしばしば不可触賤の実践と下層カースト市民からの距離に関連していた。[518]

迫害

Hindus have experienced both historical religious persecution, ongoing religious persecution and systematic violence. These occur in the form of forced conversions,[519][520] documented massacres,[521][522][523] demolition and desecration of temples.[524][525] Historic persecutions of Hindus happened under Muslim rulers[525][526] and also by Christian Missionaries.[527] In the Mughal Period, Hindus were forced to pay the Jizya. In Goa, the 1560 inquisition by Portuguese colonists is also considered one of the most brutal persecutions of Hindus.[528] Between 200,000 and one million people, including both Muslims and Hindus, were killed during the Partition of India.[529] In modern times, Hindus face discrimination in many parts of the world and also face persecution and forced conversion[530] in many countries, especially in Pakistan, Bangladesh, Fiji and others.[531][532]

Conversion debate

In the modern era, religious conversion from and to Hinduism has been a controversial subject. Some state the concept of missionary conversion, either way, is anathema to the precepts of Hinduism.[533]

It is known that, unlike ethnic religions, which exist almost exclusively among, for instance, the Japanese (Shinto), the Chinese (Taoism), or the Jews (Judaism), Hinduism in India and Nepal is widespread among many, both Indo-Aryan and non-Aryan ethnic groups. In addition, religious conversion to Hinduism has a long history outside India. Merchants and traders of India, particularly from the Indian peninsula, carried their religious ideas, which led to religious conversions to Hinduism outside India. In antiquity and the Middle Ages, Hinduism was the state religion in many kingdoms of Asia, the so-called Greater India: from Afghanistan (Kabul) in the West and including almost all of Southeast Asia in the East (Cambodia, Vietnam, Indonesia,[274][534] Philippines), and only by 15th century was nearly everywhere supplanted by Buddhism and Islam.[271][272] Therefore, it looks quite natural for the modern Hindu preaching in the world.

Within India, archeological and textual evidence such as the 2nd-century BCE Heliodorus pillar suggest that Greeks and other foreigners converted to Hinduism.[535][536] The debate on proselytization and religious conversion between Christianity, Islam and Hinduism is more recent, and started in the 19th century.[537][538][note 37]

Religious leaders of some Hindu reform movements such as the Arya Samaj launched Shuddhi movement to proselytize and reconvert Muslims and Christians back to Hinduism,[542][543] while those such as the Brahmo Samaj suggested Hinduism to be a non-missionary religion.[533] All these sects of Hinduism have welcomed new members to their group, while other leaders of Hinduism's diverse schools have stated that given the intensive proselytization activities from missionary Islam and Christianity, this "there is no such thing as proselytism in Hinduism" view must be re-examined.[533][542][544]

主要な宗教からヒンドゥー教への転換、およびその逆の転換の適切性は、インド、ネパール、[545] [546] [547]およびインドネシアで活発に議論されてきたトピックであり、現在も続いています。[548]

も参照してください

- ヒンドゥー教

- 関連するシステムと宗教

ノート

- ^ a b ヒンドゥー教は、「宗教」、「一連の宗教的信念と実践」、「宗教的伝統」、「生き方」(Sharma 2003、pp。12–13)などとしてさまざまに定義されています。トピックについては、 Flood 2008の「境界の確立」の1〜17ページを参照してください。

- ^ 西洋の言語では、ダルマを一言で翻訳することはできません。( Widgery 1930)( Rocher 2003) オックスフォード世界宗教辞典、ダルマは、ダルマを次のように定義しています。したがって、その秩序の維持に適切な行動に。」ダルマ(義、倫理)を参照してください。

- ^ a b 宗教の文脈における「ヒンドゥー」の最初の言及については、いくつかの見解があります。

- 洪水1996、p。6つの州:「アラビア語のテキストでは、アルヒンドは現代インドの人々に使用される用語であり、「ヒンドゥー」または「ヒンドゥー」は、18世紀の終わりにイギリス人によって人々を指すために使用されましたインド北西部の人々である「ヒンドゥー教徒」の'は1830年頃にヒンドゥー教徒に追加され、他の宗教とは対照的にハイカーストのブラフマンの文化と宗教を示しました。この用語は、植民地主義に反対する国民的アイデンティティを構築するという文脈で、すぐにインド人自身によって割り当てられました。 「ヒンドゥー」は、「」とは対照的に、サンスクリット語とベンガリ語のアラビア語のテキストで使用されました。

- Sharma 2002と他の学者は、7世紀の中国の学者Xuanzangは、インドへの17年間の旅行とその人々や宗教との交流が記録され、中国語で保存されていると述べています。玄奘は、西暦7世紀初頭のヒンドゥー教のデヴァ寺院、太陽神とシヴァの崇拝、ヒンドゥー教の哲学のサムキャとヴァイシェシカの学校の学者、ヒンドゥー教徒、ジャイナ教徒、仏教徒の僧侶と修道院との彼の議論について説明しています。 (大乗仏教と玄奘の両方)、そしてナランダでの仏教のテキストと一緒にヴェーダの研究。も参照してくださいGosch&Stearns 2007、pp。88–99、Sharma 2011、 pp。5–12、Smithetal 。2012年、321〜324ページ。

- Sharma 2002はまた、ムハンマド・イブン・カシムによる8世紀のアラブのシンド侵略、アル・ビルーニーの11世紀のテキストTarikh Al-Hind、およびデリー・スルタン時代のテキストなど、イスラム教のテキストでのヒンドゥーという言葉の使用についても言及しています。ここで、ヒンドゥーという用語は、仏教徒などのすべての非イスラム教徒を含み、「地域または宗教」であるという曖昧さを保持しています。

- ローレンツェン2006は、リチャード・イートンを引用して次のように述べています。イサミは、民族地理学的な意味でインド人を意味する「ヒンディー」という言葉を使用し、ヒンドゥー教の信者という意味で「ヒンドゥー」を意味する「ヒンドゥー」という言葉を使用しています。(Lorenzen 2006、p。33)

- Lorenzen 2006 、pp。32–33は、12世紀までのCanda BaradaiによるPrithvírájRásoなどの他の非ペルシャ語のテキスト、および14世紀にイスラム王朝の軍事的拡大と戦ったアンドラプラデーシュ王国からの碑文の証拠にも言及しています。ヒンズー教徒は、「トルコ人」またはイスラム教の宗教的アイデンティティとは対照的に、部分的に宗教的アイデンティティを意味します。

- Lorenzen 2006、p。15は、ヨーロッパ言語(スペイン語)での宗教的文脈での「ヒンドゥー」という言葉の最も初期の使用の1つは、1649年のセバスチャンマンリケによる出版であったと述べています。}}

- ^ 参照:

- ファウラー1997、p。1:「おそらく世界で最も古い宗教」。

- Klostermaier 2007、p。1:世界で「最古の生きている主要な宗教」。

- Kurien 2006:「地球上には10億人近くのヒンズー教徒が住んでいます。彼らは、世界最古の宗教を実践しています...」

- Bakker 1997:「それ[ヒンドゥー教]は最も古い宗教です」。

- ノーブル1998年:「世界最古の生き残った宗教であるヒンドゥー教は、南アジアの多くで日常生活の枠組みを提供し続けています。」

アニミズムは「最古の宗教」とも呼ばれています。(Sponsel2012:「アニミズムは世界で群を抜いて最古の宗教です。その古代は、少なくとも約60、000〜80、000年前のネアンデルタール人の時代にまでさかのぼると思われます。 ")

オーストラリアの言語学者であるRMWディクソンは、クレーター湖の起源に関するアボリジニの神話が1万年前に正確に遡ることができることを発見しました。(ディクソン1996)

参照: - ^ ノット1998、p。5:「多くの人がヒンドゥー教をサナタナダルマ、永遠の伝統または宗教として説明しています。これは、その起源が人類の歴史を超えているという考えを指します。」

- ^ a b Lockard 2007, p. 50: "The encounters that resulted from Aryan migration brought together several very different peoples and cultures, reconfiguring Indian society. Over many centuries a fusion of Aryan and Dravidian occurred, a complex process that historians have labeled the Indo-Aryan synthesis."

Lockard 2007, p. 52: "Hinduism can be seen historically as a synthesis of Aryan beliefs with Harappan and other Dravidian traditions that developed over many centuries." - ^ a b Hiltebeitel 2007, p. 12: "A period of consolidation, sometimes identified as one of 'Hindu synthesis', 'Brahmanic synthesis', or 'orthodox synthesis', takes place between the time of the late Vedic Upanishads (c. 500 BCE) and the period of Gupta imperial ascendency (c. 320–467 CE)."

- ^ See:

- Samuel 2008, p. 194: "The Brahmanical pattern"

- Flood 1996, p. 16: "The tradition of brahmanical orthopraxy has played the role of 'master narrative'"

- Hiltebeitel 2007, p. 12: "Brahmanical synthesis"

- ^ a b See also:

- Ghurye 1980, pp. 3–4: "He [Dr. J. H. Hutton, the Commissioner of the Census of 1931] considers modern Hinduism to be the result of an amalgam between pre-Aryan Indian beliefs of Mediterranean inspiration and the religion of the Rigveda. 'The Tribal religions present, as it were, surplus material not yet built into the temple of Hinduism'."

- Zimmer 1951, pp. 218–219.

- Sjoberg 1990, p. 43. Quote: [Tyler (1973). India: An Anthropological Perspective. p. 68.]; "The Hindu synthesis was less the dialectical reduction of orthodoxy and heterodoxy than the resurgence of the ancient, aboriginal Indus civilization. In this process the rude, barbaric Aryan tribes were gradually civilised and eventually merged with the autochthonous Dravidians. Although elements of their domestic cult and ritualism were jealously preserved by Brahman priests, the body of their culture survived only in fragmentary tales and allegories embedded in vast, syncretistic compendia. On the whole, the Aryan contribution to Indian culture is insignificant. The essential pattern of Indian culture was already established in the third millennium B.C., and ... the form of Indian civilization perdured and eventually reasserted itself."

- Sjoberg 1990.

- Flood 1996, p. 16: "Contemporary Hinduism cannot be traced to a common origin [...] The many traditions which feed into contemporary Hinduism can be subsumed under three broad headings: the tradition of Brahmanical orthopraxy, the renouncer traditions and popular or local traditions. The tradition of Brahmanical orthopraxy has played the role of 'master narrative', transmitting a body of knowledge and behaviour through time, and defining the conditions of orthopraxy, such as adherence to varnasramadharma."

- Nath 2001.

- Werner 1998.

- Werner 2005, pp. 8–9.

- Lockard 2007, p. 50.

- Hiltebeitel 2007.

- Hopfe & Woodward 2008, p. 79: "The religion that the Aryans brought with them mingled with the religion of the native people, and the culture that developed between them became classical Hinduism."

- Samuel 2010.

- ^ a b Among its roots are the Vedic religion of the late Vedic period (Flood 1996, p. 16) and its emphasis on the status of Brahmans (Samuel 2008, pp. 48–53), but also the religions of the Indus Valley Civilisation (Narayanan 2009, p. 11; Lockard 2007, p. 52; Hiltebeitel 2007, p. 3; Jones & Ryan 2007, p. xviii) the Sramana or renouncer traditions of north-east India (Flood 1996, p. 16; Gomez 2013, p. 42), with possible roots in a non-Vedic Indo-Aryan culture (Bronkhorst 2007); and "popular or local traditions" (Flood 1996, p. 16) and prehistoric cultures "that thrived in South Asia long before the creation of textual evidence that we can decipher with any confidence."Doniger 2010, p. 66)

- ^ In D. N. Jha’s essay Looking for a Hindu identity, he writes: "No Indians described themselves as Hindus before the fourteenth century" and "Hinduism was a creation of the colonial period and cannot lay claim to any great antiquity."[49] He further wrote "The British borrowed the word ‘Hindu’ from India, gave it a new meaning and significance, [and] reimported it into India as a reified phenomenon called Hinduism."[50]

- ^ The Indo-Aryan word Sindhu means "river", "ocean".[41] It is frequently being used in the Rigveda. The Sindhu-area is part of Āryāvarta, "the land of the Aryans".

- ^ In ancient literature the name Bharata or Bharata Vrasa was being used.[55]

- ^ In the contemporary era, the term Hindus are individuals who identify with one or more aspects of Hinduism, whether they are practicing or non-practicing or Laissez-faire.[57] The term does not include those who identify with other Indian religions such as Buddhism, Jainism, Sikhism or various animist tribal religions found in India such as Sarnaism.[58] The term Hindu, in contemporary parlance, includes people who accept themselves as culturally or ethnically Hindu rather than with a fixed set of religious beliefs within Hinduism. One need not be religious in the minimal sense, states Julius Lipner, to be accepted as Hindu by Hindus, or to describe oneself as Hindu.[59]

- ^ Sweetman mentions:

- Halbfass 1988, India and Europe

- Sontheimer 1989, Hinduism Reconsidered

- Ronald Inden, Imagining India

- Carol Breckenridge and Peter van der Veer, Orientalism and the Postcolonial Predicament

- Vasudha Dalmia and Heinrich von Stietencron, Representing Hinduism

- S.N. Balagangadhara, The Heathen in his Blindness...

- Thomas Trautmann, Aryans and British India

- King 1999, Orientalism and religion

- ^ See Rajiv Malhotra and Being Different for a critic who gained widespread attention outside the academia, Invading the Sacred, and Hindu studies.

- ^ The term sanatana dharma and its Vedic roots had another context in the colonial era, particularly the early 19th-century through movements such as the Brahmo Samaj and the Arya Samaj. These movements, particularly active in British and French colonies outside India, such as in Africa and the Caribbean, interpreted Hinduism to be a monotheistic religion and attempted to demonstrate that it to be similar to Christianity and Islam. Their views were opposed by other Hindus such as the Sanatan Dharma Sabha of 1895.[87]

- ^ Lipner quotes Brockington (1981), The sacred tread, p. 5.

- ^ Hinduism is derived from Persian hindu- and the -ism suffix. It is first recorded in 1786, in the generic sense of "polytheism of India".[web 8]

- ^ Pennington[139] describes the circumstances in which early impressions of Hinduism were reported by colonial era missionaries: "Missionary reports from India also reflected the experience of foreigners in a land whose native inhabitants and British rulers often resented their presence. Their accounts of Hinduism were forged in physically, politically and spiritually hostile surroundings [impoverished, famine-prone Bengal – now West Bengal and Bangladesh]. Plagued with anxieties and fears about their own health, regularly reminded of colleagues who had lost their lives or reason, uncertain of their own social location, and preaching to crowds whose reactions ranged from indifference to amusement to hostility, missionaries found expression for their darker misgivings in their production of what is surely part of their speckled legacy: a fabricated Hinduism crazed by blood-lust and devoted to the service of devils."

- ^ Sweetman (2004, p. 13) identifies several areas in which "there is substantial, if not universal, an agreement that colonialism influenced the study of Hinduism, even if the degree of this influence is debated":

- The wish of European Orientalists "to establish a textual basis for Hinduism", akin to the Protestant culture,(Sweetman 2004, p. 13) which was also driven by preference among the colonial powers for "written authority" rather than "oral authority".(Sweetman 2004, p. 13)

- The influence of Brahmins on European conceptions of Hinduism.(Sweetman 2004, p. 13)

- [T]he identification of Vedanta, more specifically Advaita Vedanta, as 'the paradigmatic example of the mystical nature of the Hindu religion'.(Sweetman 2004, p. 13) (Sweetman cites King 1999, p. 128.) Several factors led to the favouring of Vedanta as the "central philosophy of the Hindus":(Sweetman 2004, pp. 13–14)

- According to Niranjan Dhar's theory that Vedanta was favored because British feared French influence, especially the impact of the French Revolution; and Ronald Inden's theory that Advaita Vedanta was portrayed as 'illusionist pantheism' reinforcing the colonial stereotypical construction of Hinduism as indifferent to ethics and life-negating.(Sweetman 2004, pp. 13–14)

- "The amenability of Vedantic thought to both Christian and Hindu critics of 'idolatry' in other forms of Hinduism".(Sweetman 2004, p. 14)

- The colonial constructions of caste as being part of Hinduism.(Sweetman 2004, pp. 14–16) According to Nicholas Dirks' theory that, "Caste was refigured as a religious system, organising society in a context where politics and religion had never before been distinct domains of social action. (Sweetman cites Dirks 2001, p. xxvii.)

- "[T]he construction of Hinduism in the image of Christianity"(Sweetman 2004, p. 15)

- Anti-colonial Hindus(Sweetman 2004, pp. 15–16) "looking toward the systematisation of disparate practices as a means of recovering a pre-colonial, national identity".(Sweetman 2004, p. 15) (Sweetman cites Viswanathan 2003, p. 26.)

- ^ Many scholars have presented pre-colonial common denominators and asserted the importance of ancient Hindu textual sources in medieval and pre-colonial times:

- Klaus Witz[142] states that Hindu Bhakti movement ideas in the medieval era grew on the foundation of Upanishadic knowledge and Vedanta philosophies.

- John Henderson[143] states that "Hindus, both in medieval and in modern times, have been particularly drawn to those canonical texts and philosophical schools such as the Bhagavad Gita and Vedanta, which seem to synthesize or reconcile most successfully diverse philosophical teachings and sectarian points of view. Thus, this widely recognized attribute of Indian culture may be traced to the exegetical orientation of medieval Hindu commentarial traditions, especially Vedanta.

- Patrick Olivelle[144] and others[145][146][147] state that the central ideas of the Upanishads in the Vedic corpus are at the spiritual core of Hindus.

- ^ a b * Hinduism is the fastest growing religion in Russia, Ghana and United States. This was due to the influence of the ISKCON and the migration of Hindus in these nations.[154]

- In western nations, the growth of Hinduism has been very fast and is the second fastest growing religion in Europe, after Islam.[155]

- ^ For translation of deva in singular noun form as "a deity, god", and in plural form as "the gods" or "the heavenly or shining ones", see: Monier-Williams 2001, p. 492. For translation of devatā as "godhead, divinity", see: Monier-Williams 2001, p. 495.

- ^ Among some regional Hindus, such as Rajputs, these are called Kuldevis or Kuldevata.[216]

- ^ According to Jones & Ryan 2007, pp. 474, "The followers of Vaishnavism are many fewer than those of Shaivism, numbering perhaps 200 million."[247][dubious ]

- ^ sometimes with Lakshmi, the spouse of Vishnu; or, as Narayana and Sri;[250]

- ^ Rigveda is not only the oldest among the vedas, but is one of the earliest Indo-European texts.

- ^ According to Bhavishya Purana, Brahmaparva, Adhyaya 7, there are four sources of dharma: Śruti (Vedas), Smṛti (Dharmaśāstras, Puranas), Śiṣṭa Āchāra/Sadāchara (conduct of noble people) and finally Ātma tuṣṭi (Self satisfaction). From the sloka:

- वेदः स्मृतिः सदाचारः स्वस्य च प्रियमात्मनः । एतच्चतुर्विधं प्राहुः साक्षाद्धर्मस्य लक्षणम् ॥[web 14]

- vedaḥ smṛtiḥ sadācāraḥ svasya ca priyamātmanah

etaccaturvidham prāhuḥ sākshāddharmasya lakshaṇam - – Bhavishya Purāṇa, Brahmaparva, Adhyāya 7

- ^ Klostermaier: "Brahman, derived from the root bŗh = to grow, to become great, was originally identical with the Vedic word, that makes people prosper: words were the pricipan means to approach the gods who dwelled in a different sphere. It was not a big step from this notion of "reified speech-act" to that "of the speech-act being looked at implicitly and explicitly as a means to an end." Klostermaier 2007, p. 55 quotes Madhav M. Deshpande (1990), Changing Conceptions of the Veda: From Speech-Acts to Magical Sounds, p.4.

- ^ The cremation ashes are called phool (flowers). These are collected from the pyre in a rite-of-passage called asthi sanchayana, then dispersed during asthi visarjana. This signifies redemption of the dead in waters considered to be sacred and a closure for the living. Tirtha locations offer these services.[372][373]

- ^ Venkataraman and Deshpande: "Caste-based discrimination does exist in many parts of India today.... Caste-based discrimination fundamentally contradicts the essential teaching of Hindu sacred texts that divinity is inherent in all beings."[web 21]

- ^ For instance Fowler: "probably the oldest religion in the world"[466]

- ^ Among its roots are the Vedic religion[114] of the late Vedic period and its emphasis on the status of Brahmans,[469] but also the religions of the Indus Valley Civilisation,[28][470][471] the Sramana[472] or renouncer traditions[114] of east India,[472] and "popular or local traditions".[114]

- ^ There is no exact dating possible for the beginning of the Vedic period. Witzel mentions a range between 1900 and 1400 BCE.[474] Flood mentions 1500 BCE.[475]

- ^ Réunion is not a country, but an independent French terretory.

- ^ The controversy started as an intense polemic battle between Christian missionaries and Muslim organizations in the first half of the 19th century, where missionaries such as Karl Gottlieb Pfander tried to convert Muslims and Hindus, by criticizing Qur'an and Hindu scriptures.[538][539][540][541] Muslim leaders responded by publishing in Muslim-owned newspapers of Bengal, and through rural campaign, polemics against Christians and Hindus, and by launching "purification and reform movements" within Islam.[537][538] Hindu leaders joined the proselytization debate, criticized Christianity and Islam, and asserted Hinduism to be a universal, secular religion.[537][542]

References

- ^ "Hinduism". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved 19 April 2021.

- ^ "Hindu Countries 2021". World Population Review. 2021. Retrieved 2 June 2021.

- ^ Siemens & Roodt 2009, p. 546.

- ^ Leaf 2014, p. 36.

- ^ Knott 1998, pp. 3, 5.

- ^ a b c Hatcher 2015, pp. 4–5, 69–71, 150–152.

- ^ Bowker 2000.

- ^ Harvey 2001, p. xiii.

- ^ a b Smith, Brian K. (1998). "Questioning Authority: Constructions and Deconstructions of Hinduism". International Journal of Hindu Studies. 2 (3): 313–339. doi:10.1007/s11407-998-0001-9. JSTOR 20106612. S2CID 144929213.

- ^ a b Sharma & Sharma 2004, pp. 1–2.

- ^ a b Klostermaier 2014, p. 2.

- ^ a b Klostermaier 2007b, p. 7.

- ^ a b Sharma, A (1985). "Did the Hindus have a name for their own religion?". The Journal of the Oriental Society of Australia. 17 (1): 94–98 [95].

- ^ "View Dictionary". sanskritdictionary.com. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ a b c Michaels 2004.

- ^ a b Bilimoria 2007; see also Koller 1968.

- ^ a b Flood 1997, p. 11.

- ^ a b Klostermaier 2007, pp. 46–52, 76–77.

- ^ a b c Brodd 2003.

- ^ Dharma, Samanya; Kane, P. V. History of Dharmasastra. Vol. 2. pp. 4–5. See also Widgery 1930

- ^ a b Ellinger, Herbert (1996). Hinduism. Bloomsbury Academic. pp. 69–70. ISBN 978-1-56338-161-4.

- ^ Zaehner, R. C. (1992). Hindu Scriptures. Penguin Random House. pp. 1–7. ISBN 978-0-679-41078-2.

- ^ a b Clarke, Matthew (2011). Development and Religion: Theology and Practice. Edward Elgar Publishing. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-85793-073-6. Archived from the original on 29 December 2020. Retrieved 11 February 2015.

- ^ Holberg, Dale, ed. (2000). Students' Britannica India. Vol. 4. Encyclopædia Britannica India. p. 316. ISBN 978-0-85229-760-5.

- ^ Nicholson, Andrew (2013). Unifying Hinduism: Philosophy and Identity in Indian Intellectual History. Columbia University Press. pp. 2–5. ISBN 978-0-231-14987-7.

- ^ a b Samuel 2008, p. 193.

- ^ a b Hiltebeitel 2007, p. 12; Flood 1996, p. 16; Lockard 2007, p. 50

- ^ a b c d Narayanan 2009, p. 11.

- ^ a b Fowler 1997, pp. 1, 7.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Hiltebeitel 2007, p. 12.

- ^ a b c d Larson 2009.

- ^ a b Larson 1995, pp. 109–111.

- ^ a b c Bhandarkar 1913.

- ^ a b c Tattwananda n.d.

- ^ a b c Flood 1996, pp. 113, 134, 155–161, 167–168.

- ^ a b c Lipner 2009, pp. 377, 398.

- ^ Frazier, Jessica (2011). The Continuum companion to Hindu studies. London: Continuum. pp. 1–15. ISBN 978-0-8264-9966-0.

- ^ "Peringatan". sp2010.bps.go.id.

- ^ Vertovec, Steven (2013). The Hindu Diaspora: Comparative Patterns. Routledge. pp. 1–4, 7–8, 63–64, 87–88, 141–143. ISBN 978-1-136-36705-2.

- ^ – "Hindus". Pew Research Center's Religion & Public Life Project. 18 December 2012. Archived from the original on 9 February 2020. Retrieved 14 February 2015.

– "Table: Religious Composition by Country, in Numbers (2010)". Pew Research Center's Religion & Public Life Project. 18 December 2012. Archived from the original on 1 February 2013. Retrieved 14 February 2015. - ^ a b Flood 2008, p. 3.

- ^ a b c d e f g Flood 1996, p. 6.

- ^ Parpola 2015, "Chapter 1".

- ^ Parpola (2015), "Chapter 9": "In Iranian languages, Proto-Iranian *s became h before a following vowel at a relatively late period, perhaps around 850–600 BCE."

- ^ a b c Singh 2008, p. 433.

- ^ Doniger 2014, p. 5.

- ^ Parpola 2015, p. 1.

- ^ a b Doniger 2014, p. 3.

- ^ a b "A short note on the short history of Hinduism".

- ^ "Short note on the short history of Hinduism".

- ^ a b c Sharma 2002.

- ^ Thapar, Romila (2004). Early India: From the Origins to A.D. 1300. University of California Press. p. 38. ISBN 978-0-520-24225-8.

- ^ Thapar 1993, p. 77.

- ^ Thompson Platts 1884.

- ^ Garg, Gaṅgā Rām (1992). Encyclopaedia of the Hindu World, Volume 1. Concept Publishing Company. p. 3. ISBN 978-81-7022-374-0.

- ^ O'Conell, Joseph T. (1973). "The Word 'Hindu' in Gauḍīya Vaiṣṇava Texts". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 93 (3): 340–344. doi:10.2307/599467. JSTOR 599467.

- ^ Turner, Bryan (2010). The New Blackwell Companion to the Sociology of Religion. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 424–425. ISBN 978-1-4051-8852-4.

- ^ Minahan, James (2012). Ethnic Groups of South Asia and the Pacific: An Encyclopedia. pp. 97–99. ISBN 978-1-59884-659-1.

- ^ Lipner 2009, p. 8.

- ^ a b Sweetman, Will (2003). Mapping Hinduism: 'Hinduism' and the Study of Indian Religions, 1600–1776. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 163, 154–168. ISBN 978-3-931479-49-7.

- ^ a b Lipner 2009, p. 8 Quote: "[...] one need not be religious in the minimal sense described to be accepted as a Hindu by Hindus, or describe oneself perfectly validly as Hindu. One may be polytheistic or monotheistic, monistic or pantheistic,henotheistic, panentheistic ,pandeistic, even an agnostic, humanist or atheist, and still be considered a Hindu."

- ^ Kurtz, Lester, ed. (2008). Encyclopedia of Violence, Peace and Conflict. Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-369503-1.

- ^ MK Gandhi, The Essence of Hinduism Archived 24 July 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Editor: VB Kher, Navajivan Publishing, see page 3; According to Gandhi, "a man may not believe in God and still call himself a Hindu."

- ^ Knott 1998, p. 117.

- ^ Sharma 2003, pp. 12–13.

- ^ Radhakrishnan & Moore 1967, p. 3; Witzel 2003, p. 68

- ^ a b Sweetman 2004.

- ^ a b c d King 1999.

- ^ Nussbaum 2009.

- ^ Flood 1996, p. 14.

- ^ a b June McDaniel "Hinduism", in Corrigan, John (2007). The Oxford Handbook of Religion and Emotion. Oxford University Press. pp. 52–53. ISBN 978-0-19-517021-4.

- ^ Michaels 2004, p. 21.

- ^ Michaels 2004, p. 22.

- ^ a b Michaels 2004, p. 23.

- ^ a b c Michaels 2004, p. 24.

- ^ "Definition of RAMAISM". www.merriam-webster.com. Archived from the original on 29 December 2020. Retrieved 28 October 2020.

- ^ Michaels 2004, pp. 21–22.

- ^ Michaels 2004, pp. 22–23.

- ^ a b c d Ronald Inden (2001), Imagining India, Indiana University Press, ISBN 978-0-253-21358-7, pp. 117–122, 127–130

- ^ Insoll, Timothy (2001). Archaeology and world religion. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-22155-9. Archived from the original on 29 December 2020. Retrieved 29 December 2020.

- ^ Bowker 2000; Harvey 2001, p. xiii

- ^ Vivekjivandas 2010, p. 1.

- ^ Knott 1998, p. 111.

- ^ Hacker, Paul (2006). "Dharma in Hinduism". Journal of Indian Philosophy. 34 (5): 479–496. doi:10.1007/s10781-006-9002-4. S2CID 170922678.

- ^ Knott 1998, p. 3.

- ^ a b c d e Lipner 2009, pp. 15–17.

- ^ Taylor, Patrick; Case, Frederick I. (2013). The Encyclopedia of Caribbean Religions: Volume 1: A – L; Volume 2: M – Z. University of Illinois Press. pp. 902–903. ISBN 978-0-252-09433-0.

- ^ Lipner 2009, p. 16.

- ^ Michaels 2004, p. 18; see also Lipner 2009, p. 77; and Smith, Brian K. (2008). "Hinduism". In Neusner, Jacob (ed.). Sacred Texts and Authority. Wipf and Stock Publishers. p. 101.

- ^ Feuerstein 2002, p. 600.

- ^ Clarke 2006, p. 209.

- ^ a b Lorenzen 2002, p. 33.

- ^ a b c d Flood 1996, p. 258.

- ^ Flood 1996, pp. 256–261.

- ^ Young, Serinity (2007). Hinduism. Marshall Cavendish. p. 87. ISBN 978-0-7614-2116-0. Retrieved 19 February 2015.

Rammohun Roy Father of Hindu Renaissance.

- ^ Flood 1996, p. 257.

- ^ Flood 1996, p. 259.

- ^ Flood 1996, p. 249.

- ^ a b c d e Flood 1996, p. 265.

- ^ a b c Flood 1996, p. 267.

- ^ Flood 1996, pp. 267–268.

- ^ Derrett, J.; Duncan, M. (1973). Dharmaśāstra and juridical literature. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. ISBN 978-3-447-01519-6. OCLC 1130636.

- ^ Doniger 2014, p. 20.

- ^ Turner 1996a, p. 275.

- ^ Ferro-Luzzi (1991). "The Polythetic-Prototype Approach to Hinduism". In Sontheimer, G.D.; Kulke, H. (eds.). Hinduism Reconsidered. Delhi: Manohar. pp. 187–95.

- ^ Dasgupta, Surendranath; Banarsidass, Motilall (1992). A history of Indian philosophy (part 1). p. 70.

- ^ Chande, M.B. (2000). Indian Philosophy in Modern Times. Atlantic Publishers & Dist. p. 277.

- ^ Culp, John (4 December 2008). Edward N. Zalta (ed.). "Panentheism". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2017 Edition). Archived from the original on 29 December 2020. Retrieved 29 December 2020.

- ^ Smith, W. C. (1962). The Meaning and End of Religion. San Francisco: Harper and Row. p. 65. ISBN 978-0-7914-0361-7. Archived from the original on 2 April 2020. Retrieved 27 October 2015.

- ^ Halbfass 1991, pp. 1–22.

- ^ Klostermaier 1994, p. 1.

- ^ Flood 1996, pp. 1, 7.

- ^ Lockard 2007, p. 50; Hiltebeitel 2007, p. 12

- ^ a b c d e Flood 1996, p. 16.

- ^ Quack, Johannes; Binder, Stefan (22 February 2018). "Atheism and Rationalism in Hinduism". Oxford Bibliographies. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/obo/9780195399318-0196.

- ^ a b c d Halbfass 1991, p. 15.

- ^ a b c Nicholson 2010.

- ^ Flood 1996, p. 35.

- ^ a b Pinkney, Andrea (2014). Turner, Bryan; Salemink, Oscar (eds.). Routledge Handbook of Religions in Asia. Routledge. pp. 31–32. ISBN 978-0-415-63503-5.

- ^ Haines, Jeffrey (2008). Routledge Handbook of Religion and Politics. Routledge. p. 80. ISBN 978-0-415-60029-3.

- ^ Halbfass 1991, p. 1.

- ^ Deutsch & Dalvi 2004, pp. 99–100.

- ^ Deutsch & Dalvi 2004, pp. 100–101.

- ^ Deutsch & Dalvi 2004, p. 101.

- ^ Nicholson 2010, p. 2; Lorenzen 2006, pp. 1–36

- ^ Lorenzen 2006, p. 36.

- ^ a b Lorenzen 1999, p. 648.

- ^ Lorenzen 1999, pp. 648, 655.

- ^ Nicholson 2010, p. 2.

- ^ Burley 2007, p. 34.

- ^ Lorenzen 2006, pp. 24–33.

- ^ Lorenzen 2006, p. 27.

- ^ Lorenzen 2006, pp. 26–27.

- ^ Michaels 2004, p. 44.

- ^ Hackel in Nicholson 2010.

- ^ King 2001.

- ^ a b King 1999, pp. 100–102.

- ^ Sweetman 2004, pp. 14–15.

- ^ Pennington 2005, pp. 76–77.

- ^ King 1999, p. 169.

- ^ a b Pennington 2005, pp. 4–5 and Chapter 6.

- ^ Witz, Klaus G (1998). The Supreme Wisdom of the Upaniṣads: An Introduction, Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 10–11. ISBN 978-81-208-1573-5.

- ^ Henderson, John (2014). Scripture, Canon and Commentary. Princeton University Press. p. 120. ISBN 978-0-691-60172-4.

- ^ a b Olivelle, Patrick (2014). The Early Upanisads. Oxford University Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-19-535242-9.

Even though theoretically the whole of Vedic corpus is accepted as revealed truth [shruti], in reality it is the Upanishads that have continued to influence the life and thought of the various religious traditions that we have come to call Hindu. Upanishads are the scriptures par excellence of Hinduism.